A UCHealth remote patient monitoring program introduced last spring to protect recovering COVID-19 patients after they return home continues to blossom.

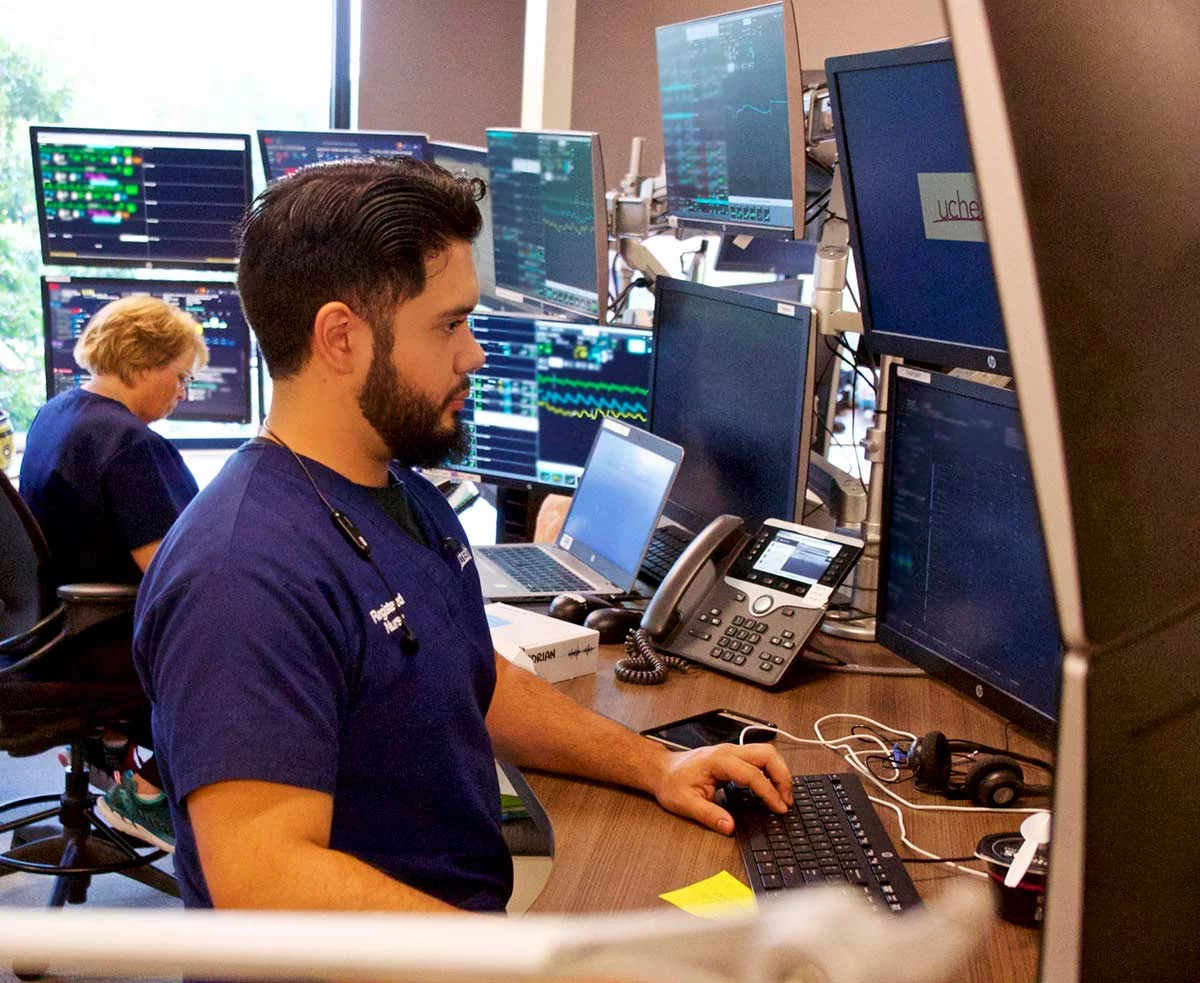

The initiative centers around an FDA-approved device, fitted to the wrist and finger, that allows providers in UCHealth’s Virtual Health Center to monitor patients’ oxygen levels, heart rates and respiratory rates from afar. Patients transmit the biometric information wirelessly through an app downloaded to their smartphones to a cloud server for continuous monitoring. If providers see a worrisome sign, such as declining oxygen levels, they can quickly intervene to head off the need for an emergency room trip or hospitalization.

Use of remote patient monitoring devices expands

The remote patient monitoring program launched last April, enrolling patients at UCHealth’s University of Colorado Hospital and Greeley Hospital, where numbers of COVID-19 cases were high. UCHealth’s Memorial Hospital Central and Memorial Hospital North in Colorado Springs are also using remote patient monitors.

The idea is to distribute the devices where the need is greatest, said Amy Hassell, a critical-care nurse and director of patient services for the Virtual Health Center.

“We’ve targeted the program to where the number of patients is highest and the hospital capacity is the lowest,” Hassell said.

The program initially enrolled only selected inpatients ready for discharge. It has now expanded to the emergency departments at UCH and Memorial, another important step to manage hospital capacity, Hassell said. As of Jan. 14, the number of patients hospitalized for COVID-19 illness across UCHealth hospitals was 202, a significant decrease from a high of 469 hospitalized patients in late fall.

“If patients with COVID-19 come into the ED needing oxygen, we can watch over them at home while they recover there,” she explained. “That avoids hospital admission.”

An aid for minimizing risk and managing capacity

With nine months of experience, the Virtual Health Center’s confidence in the remote monitoring device has grown. The program is now in a second phase, said Dr. Hemali Patel, a hospitalist at UCH who worked with clinical colleagues to develop it.

Patel said in the first phase, the program prioritized monitoring patients most at risk from COVID-19. The list included patients with comorbidities, like diabetes; those who were immunocompromised; those 55 years or older; and those who required high levels of oxygen. The idea was to provide a layer of reassurance through the device for providers worried about discharging their sickest patients – particularly with a new and poorly understood disease.

“When we first started using remote patient monitoring in the spring, COVID-19 was new, and I think a lot of us didn’t know what to anticipate for patients once they left the hospital,” Patel said. “We were really figuring out how to do right by our patients without jeopardizing their safety. We set out to protect them from adverse events, and I think we accomplished that.”

With the second wave of the pandemic, and a sharp increase in the number of hospitalized patients, the program now emphasizes using remote monitoring to manage capacity, Patel said. Rather than focusing solely on the sickest patients, providers are now identifying patients they can send home a half-day or a day earlier with the protection of remote monitoring. That frees up beds for patients who truly need to be hospitalized, she explained.

“We’ve shifted from a reassurance model to a capacity management model, while we use the same technology,” Patel said.

Positive data results

She emphasized that experience backs up the shift. Data from the first group of prioritized patients, for example, showed their 30-day rehospitalization and emergency department visit rates were no higher than for COVID-19 patients as a whole. In addition, hospitals have learned much more about treating COVID-19 and managing its symptoms.

“This time around, I think we know more about what to do with COVID,” Patel said. “We can now anticipate a little about what patients will experience once they leave the hospital.”

The result: increased confidence among providers that their patients can go home safely. (Watch this video to see how a sense of teamwork among UCHealth care givers has never been stronger.)

“The feedback from our front-line physicians is that they are so glad to have one additional tool in place to keep patients safe,” she said.

Hassell said most patients have readily embraced the program. The Virtual Health Center has provided successful early medical assistance to about a dozen patients discharged with the monitoring devices.

The patient verdict on the Masimo monitoring devices and the program as a whole has been overwhelmingly positive, Hassell said. UCHealth is also using BioIntelliSense stickers to monitor vital signs remotely.

“Patients love the monitoring and are so grateful for having the comfort of someone checking in on them,” she said.

A patient’s scary COVID-19 experience

That group would include Sherri Thornton of Denver. Thornton saw COVID-19 strike at least two people close to her before she too caught the disease. She spent six days in November, including Thanksgiving, at UCH for treatment before returning home with the remote monitoring device. She was able to take it off in mid-December, but her recovery proceeds slowly.

“This virus is no joke,” Thornton said. “People don’t realize it’s real.”

Thornton, 56, didn’t have to be convinced to guard against infection. In March, her oldest sister fell seriously ill to COVID-19 and is still recovering. In November, one of Thornton’s co-workers at a church-run learning center where she works with 4-year-olds tested positive for the disease and also became very sick.

The school immediately shut down the team’s three rooms after the co-worker’s diagnosis. Thornton got a COVID-19 test that came back positive, but she said she felt symptoms before she got the results. She lost her sense of taste and smell; developed a dry, crackly cough that ultimately produced gray phlegm; and ran a fever that reached 101.

The virus eventually produced “crazy” body aches that made it hard for her to walk. A week after getting the test, Thornton got up to take a shower, but got so weak she had to sink down in the tub to avoid falling. She struggled to get out and dry herself, then crawled back to her room to get her clothes on, all the while gasping for air.

A rush to the hospital

Thornton was alone, having quarantined to protect her husband from infection after her co-worker’s diagnosis, so she called the parents of one of her school children for help. With much effort she got out of her condo to the car and went to the emergency department at UCH, where she got oxygen, a chest X-ray and a blood draw. The news wasn’t good: her blood oxygen level was 83, well below the desirable mid-90s, and she had pneumonia.

The hospital admitted Thornton and treated her with the steroid dexamethasone and six liters of oxygen. By the fourth day, she was able to breathe on her own, as long as she didn’t move, but she needed oxygen to inch to the bathroom. She went home Nov. 30, 2020 with supplemental oxygen, a spirometer for breathing exercises and the monitoring device.

Another pair of eyes for safety

On her third day home, Thornton said the device detected early in the evening that her oxygen level had dropped. The Virtual Health Center called to check on her and also let her sister, Thornton’s emergency contact, know they’d noticed the change. Thornton put her supplemental oxygen on, changed a strip on the remote device’s finger monitor and got her levels back to normal.

She no longer needs the device but said she still has a long way back to her pre-COVID status. She fatigues easily and doesn’t anticipate getting back to work at the school until the end of January at the earliest.

“If I go four or five hours [of activity], my body lets me know I’ve done too much,” Thornton said. “Four-year-olds have a lot of energy. I have to make sure I’m up to it.”

COVID-19 remains an unpredictable disease, and Thornton’s experience with it underscores the importance of providers guarding patients after they leave the hospital.

“Recovery is a process, day by day,” Thornton said. “You can’t just pick up where you left off and go back. You have no idea what that virus can do to you.”

She is grateful that she had the extra pair of eyes the monitoring device and the Virtual Health Center put on her.

“The device was amazing. It knew when my breathing changed,” she said. “It is something very good to have in place for people with the virus to go home with. If something happens, they know. That’s a good thing. I definitely needed it.”

Next steps for the Virtual Health Center

With the experience of caring for more patients like Sherri Thornton, the Virtual Health Center is now working on spreading what they have learned. Hassell said the center is working with Oklahoma University Medical Center to get a remote patient monitoring program up and running.

“We’ve shared our protocols and procedures to help a fellow academic medical center,” she said.

The effort goes beyond monitoring COVID-19 patients, Hassell added. For example, the Virtual Health Center is now working with a small group of diabetes patients on round-the-clock tracking of blood sugar levels measured through glucometers and transmitted back to watchful providers and staff.

“We can look at the data every day and help patients make adjustments as needed,” Hassell said. With more consistent blood sugar control, patients could avoid unnecessary emergency department trips and hospitalizations.

Expect to see more patients wearing monitoring devices, for more conditions, as the technology develops, Hassell said.

“The whole idea of remote patient monitoring is part of the future of UCHealth,” she said. “We’re trying to bring more data points to watch over patients in the home setting, where they want to be, and then apply the right wearable that makes sense for their case.”