Miguel Serrano came to the United States from Puerto Rico in the 1960s as a self-described skinny kid who didn’t know any English. His father was a boxer with the U.S. Army, but Miguel realized he’d have to stand up for himself.

With English being his second language, he got into a lot of fights. One day after he’d had to physically defend himself, his mom told him that the Bible says to turn the other cheek. His response was, “Yeah, but he hit me in the nose and I only have one nose, so I had to hit him back.”

Serrano became friends with a kid named Ronnie, and the two were a good physical match for wrestling and roughhousing. Eventually, though, Ronnie began getting the best of Miguel, who wondered how he was doing it. I’m learning karate, his friend told him. Miguel decided to check out the ancient martial art himself.

That was 51 years ago. “I fell in love with it,” says Serrano, now 66. “I never stopped. I never looked back.”

He continued practicing and teaching karate through his Air Force career and a job with the Puerto Rico Tourism Bureau in the mid-80s. Rather than taking a promotion and relocating to Los Angeles with the bureau, Serrano moved to Colorado Springs in 1992 and managed a karate school for four years. He then opened his own martial arts school, the United States Karate Academy.

That was more than 20 years ago, and the school has dojos (academies) in three Colorado Springs locations. Recently, Serrano trained with Okinawan martial arts masters in Fulton, New York. He was invited to travel to Okinawa, an island off the southern tip of Japan, to train and potentially test for the next rank level. The COVID-19 pandemic put that on indefinite hold, but he hopes one day to make the trip. Beyond that, he plans a trip with some of his students to Okinawa in 2023 to celebrate the 60th anniversary of the Okinawa Goju-Ryu Shobukan, the karate-teaching organization with which the United States Karate Academy is affiliated.

It isn’t surprising that Serrano is still working to improve his martial arts skills. After all, he’s been at it for more than half a century. One could be excused, however, for assuming that advanced heart failure might have stopped him in his tracks. Think again.

A sudden attack on his quality of life

Serrano was living in Tucson, Arizona in 2016 with his wife, Kate, and fraternal twins Cruz and Marisol, then 13 months old. Kate had headed to the airport for a business trip, so he was handling the solo parenting duties. He grabbed one kid under each arm and went to the bedroom to give them some milk. It was a beautiful day, and he thought he might feed them outside. Suddenly, though, he felt uncomfortable. He figured it might be hunger, indigestion or too much coffee, but eating half an apple didn’t help. He finally lay down on the tile floor, covered in a cold sweat.

Realizing he could be in trouble, Serrano called his in-laws, who in turn called 911 and raced over to watch the twins while he was transported to the hospital. Kate’s father contacted her prior to boarding the airplane to let her know that she needed to get back right away.

“I guess that was the first sign of seriousness,” Serrano said. However, he didn’t feel chest pressure and rode to the hospital still thinking that everything would be okay. That would not be the case.

Serrano went immediately to a hospital operating room, where he had three stents implanted to open up arteries to his heart. He needed more, but the surgeon explained that placing them would require too much dye, and he’d have to do them later. He went home, did his cardiac rehab, and walked at least a mile a day. But he didn’t feel much better, and he returned to the hospital to have four more stents put in – now seven in all.

“I thought my life was going to be fine and I would be great again, but it didn’t happen,” Serrano said. He was constantly fatigued and short of breath. A short walk with his in-laws while pushing the twins in a double stroller left him exhausted.

The steady slide experienced by heart failure patients

When Kate accepted a job in Los Alamos, New Mexico, northwest of Santa Fe, Serrano stayed behind to take care of the kids with everyday help from his in-laws. He also got a defibrillator implanted to guard against an irregular heartbeat.

“I felt like I was ‘Super Dad’ and could handle it all, but the reality was I felt every bit of what had happened to me,” Serrano said.

He was also frustrated by a lack of details about his condition from his physician in Tucson. “He told me, ‘You just had a doozy,’” recalled Serrano, who wanted specifics: if he was going to die, and if so, how much time did he have. “He never at any time seemed to give me any kind of information that was factual.”

After moving to Los Alamos, Serrano felt worse. “Eventually I got so bad I couldn’t take two steps going down a stairway without having to sit down,” he said. With Kate away on a trip one day, Serrano felt like he was having a heart attack, called 911 and rode a chopper to Albuquerque, where he spent four sleepless days hospitalized and gained 11 pounds due to fluid buildup.

Nonetheless, Serrano called the move to Los Alamos “the next to best thing that ever happened to me.” At Los Alamos Medical Center, he found cardiologist Dr. Carolyn A. Linnebur, who told him he would need a heart transplant. Dr. Linnebur contacted Dr. Larry Allen, medical director of the Advanced Heart Failure Program at UCHealth University of Colorado Hospital on the Anschutz Medical Campus. Dr. Allen told Serrano to come to the Aurora, Colorado campus for tests, which he did, on Friday, Sept. 1, 2017.

Power of the mechanical pump, LVAD

After the tests, Serrano returned to Los Alamos, with a direction to come back in two weeks. His condition rapidly declined and earlier than expected, he got a phone call from UCH with an urgent message: You need to get back here right now. He slumped into the passenger seat next to his father-in-law, who raced six hours to the hospital. Allen told Serrano his condition was too unstable to wait for a transplant. His only option was a left ventricular assist device (LVAD) to pump blood from his failing heart.

On Sept. 19, 2017, Dr. Jay Pal, a cardiothoracic surgeon and surgical director of the Mechanical Circulatory Support Program at the University of Colorado School of Medicine, implanted the left ventricular assist device. Rather than opening Serrano’s sternum, Pal’s team performed a thoracotomy, making much smaller incisions in the lower right and lower left portions of his chest. They did so with the idea that Serrano might one day be able to go back to participating in the sport he loves, Pal said.

“We did his LVAD implant via a thoracotomy to avoid issues with his sternum healing, which would have impacted his normal activity in martial arts,” he said.

After the procedure, Serrano spent a week at UCH recovering and training with Kate to change dressings and maintain the LVAD. He was on the cusp of returning to an active life, a far cry from where he had found himself not long before. He recalled requesting a shower before the surgery and feeling the shock of seeing his emaciated body in the mirror. Just days before that, the three women who run his dojos in Colorado Springs had visited him Los Alamos, thinking that he was going to die. “They pretty much came to see me off and train with me one last time,” Serrano said.

Still supporting the dojos

Instead, he continues to write new chapters in his life. His work with the dojos continues, even with the challenges of COVID-19. Pandemic restrictions forced the academies to close their physical spaces for a time, but instruction continued.

“We anticipated (the closures) and had our instructors get prepared to provide Zoom classes during the pandemic,” Serrano said. Because of the remote classes, the academies retained the vast majority of their students, he added.

Once the academies were allowed to reopen, but with capacity restrictions, Serrano added classes while continuing to offer classes by Zoom and providing private lessons for those concerned with being around others. Serrano said he meets frequently with his dojo instructors via phone and Zoom to offer guidelines and advice. He also creates videos for them that they can use to train personally and with students.

Back to the mat with a left ventricular assist device

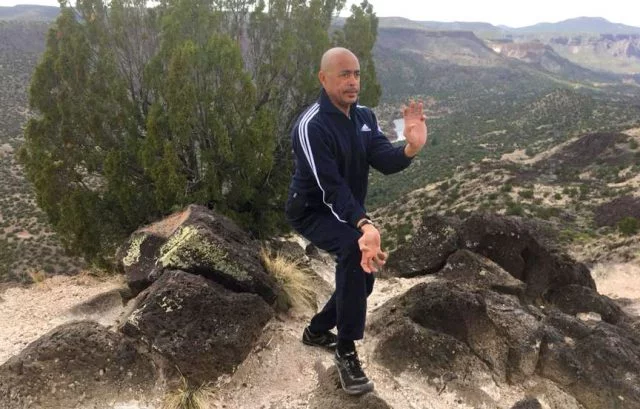

Serrano readily admits his days of jumping straight up and making simultaneous board-breaking, double jumping front kicks are over. But at the same time, he hasn’t let his left ventricular assist device sideline him. As Dr. Pal predicted, the thoracotomy greatly aided Serrano’s recovery, but when he ventured back to practicing, he initially found that wearing the pack that holds the unit’s battery and controller threw off his balance. He fixed that with a waist pack that he said is easy to wear and barely visible. And as his recent strong performance in New York with the Okinawan masters shows, he’s still got some kick left in his game.

Today, Serrano savors his second shot at life. He chuckles as his twins, who will turn 6 in April, proudly present him with handmade birthday presents and shower him with attention. “Every day I spend with these kids is one more day I’ve been blessed with life,” he said. His wife has been “a rock” of support and he’s confident in transitioning the operation of the dojos to his managers.

“I’m heavier, older, uglier and physically challenged, but I have a beautiful wife, twins and a team behind me,” Serrano said. “I look for the silver lining in every cloud.”

He’s also grateful to the UCH team he says treated him like “real family.” For Dr. Pal, Serrano’s recovery is an inspiration. From a surgical perspective, Serrano’s LVAD implant was “a pretty unremarkable case,” he said, but what he’s accomplished since the implant is another story.

“He didn’t have a lot of options,” Dr. Pal said, “but he’s now in a position to do things that patients without LVADs don’t do.”