When nurses examined Amy Davis in the emergency room in Estes Park, she thought she’d emerged from a car accident pretty much unscathed.

“I was more concerned about my other family members at that time,” she said. “I thought I was OK and just being checked out.”

It turned out that Davis was experiencing a far more serious health emergency. Quick-thinking medical providers at what is now UCHealth Estes Valley Medical Center recognized the signs of a very rare type of stroke and acted immediately to get life-saving help for Davis.

When every second counts, having access to advanced trauma and stroke experts can mean the difference between recovery and lasting damage.

A crash in the mountains leads to unexpected trauma and stroke symptoms

Davis, who lives in Tennessee, was visiting her daughter and son-in-law in Estes Park when their vehicle was struck by another just outside the gates of Rocky Mountain National Park. With only one ambulance available in Estes Park and emergency crews still working to free Davis’ son-in-law from the wreckage, emergency responders transported Davis and her daughter first to the town’s hospital — a 23-bed critical access acute care facility. Shortly afterward, the ambulance transported her son-in-law to the hospital, while the North Colorado Med Evac helicopter remained on standby.

Dr. Jennifer McLellan, a general surgeon at Estes Valley Medical Center, jumped in to help three nurses and an emergency medicine doctor who were staffing the ER that day. With three patients already needing care, the arrival of Davis and her family made for an unusually busy day in the town’s small ER.

Davis’ chest and pelvis X-rays showed no signs of injuries. She had mild tachycardia (a fast heart rate) but no neck pain. Medical experts moved Davis to a smaller trauma bay to keep an eye on her while turning their attention to other family members.

“She seemed the least injured of the three,” McLellan said.

McLellan was accompanying Davis’ son-in-law, who had suffered a head injury in the crash, to the hospital’s only CT scanner for imaging.

That’s when Davis told a nurse about tingling in her right leg. The nurse rushed to alert McLellan.

“When I examined her, she could no longer move her left side,” McLellan said. “It was very concerning. She was having some sort of event, whether a stroke, hemorrhaging or something else. We knew it was something related to the trauma.”

McLellan said she briefly considered waiting for the CT scanner to open but knew it wouldn’t change the course of action. Regardless of what Davis’ scans revealed, the hospital lacked the resources of a larger hospital, like a staff neurologist, to treat what she suspected might be the diagnosis.

McLellan made a critical decision: “Let’s get her to MCR,” McLellan said, referring to UCHealth Medical Center of the Rockies, a close partner of the Estes Park hospital, and a Level I Trauma Center in Loveland, Colorado, less than a 30-minute helicopter ride away. “That’s where she needs to be ultimately.”

As the flight crew loaded Davis into the medical helicopter, McLellan called colleagues in Loveland. She talked with Dr. Christopher Mitchell, a trauma surgeon, and alerted him that the patient he was about to receive could have a large vessel occlusion, or LVO, sustained from the trauma of a vehicle crash.

Davis was showing signs of a stroke.

Quick thinking and teamwork lead to discovery and fast treatment of a trauma-induced stroke

When Mitchell got off the phone with McLellan, he began assembling his team for the incoming trauma patient. He immediately called Dr. Gautam Sachdeva, a vascular and interventional neurologist.

“One of my jobs when I get that call is to notify all of the right people and get them here quickly,” Mitchell said.

“Based on her symptoms, I’m already thinking this is a large vessel occlusion,” Sachdeva said.

Sachdeva praised his colleagues’ decisions, including McLellan’s call to transfer Davis immediately, rather than waiting to do a CT scan in Estes Park.

“That’s where the hardest calls were made, and those decisions ultimately shaped the outcome,” Sachdeva said. “Amy presented with no symptoms of a stroke when she arrived at the ER, but she did start having them, and that was an important catch.”

A large vessel occlusion is a blockage in one of the brain’s major arteries, which cuts off the blood supply necessary to keep brain cells alive.

With a stroke, acting very quickly saves brain cells. Every minute someone is suffering a blockage,1.9 million brain cells die because the lack of blood flow deprives the cells of oxygen and nutrients, Sachdeva said.

“That means you are aging 3.1 weeks every minute of a stroke, and if that transforms to hours, every hour, you could be aging by 3.6 years,” he said. “You have to save those brain cells in a timely manner to avoid irreversible deficits.”

Medical pros prepare for a rare trauma and stroke case

Davis arrived at Medical Center of the Rockies via helicopter and went straight to imaging.

Sachdeva and his stroke team were assembling when Davis’ scans popped up on his phone. He immediately saw exactly what he suspected: trauma from the car accident had resulted in a clot, which was blocking blood flow to a section of Davis’ brain.

One of the first lines of treatment for a stroke is a clot-busting drug called Tenecteplase, or TNK. Clinicians can administer it quickly and easily, but must give it within 4.5 hours of the onset of symptoms.

Davis was within that treatment window, but Mitchell decided it wasn’t the right option in her case.

A stroke caused by trauma presents unique challenges. Without scans of every part of Davis’ body, Mitchell couldn’t be sure that there weren’t internal injuries or bleeding elsewhere from the trauma — and administering TNK without that knowledge could be fatal.

Mitchell decided against the clot-busting medication and instead administered a heparin drip and aspirin.

The next step was to prepare for a procedure called a thrombectomy, during which Sachdeva would remove the blood clot from inside Davis’ carotid artery and restore blood flow.

Thanks to the seamless, quick response, Davis was in surgery in Loveland less than an hour after she first arrived at the ER in Estes Park.

Along with being a prestigious Primary Stroke Center, Medical Center of the Rockies is also a designated Thrombectomy-Capable Stroke Center, one of only approximately 300 in the United States.

And while clot-busting drugs can sometimes break up larger clots and patients often receive them prior to a thrombectomy, for those with large vessel occlusions, like Davis, a thrombectomy is often the most effective way to restore blood flow and minimize long-term deficits.

Advanced stroke care helps reverse damage from trauma-induced brain clots

When Davis woke up in the intensive care unit after the procedure, she didn’t remember much after arriving at the Estes Park ER. Her care team told her that she had suffered a stroke and that doctors restored blood flow to her brain by doing a thrombectomy.

“When I woke, I was like, what’s all the fuss about?” Davis said. “I didn’t realize the severity of what had happened to me.”

Davis’ husband flew in from Tennessee and was at her bedside by the next day.

“When this first happened, I couldn’t move my left side, and they weren’t sure what my outcome would be,” she said. “But when my husband got there, I was able to lift my left leg, and I thought, ‘This is going to be OK.’”

Neurohospitalist Dr. Brian Kaiser was monitoring Davis’ recovery and recommended inpatient rehabilitation at UCHealth Poudre Valley Hospital, 20 minutes north of Medical Center of the Rockies.

Although Davis had regained most of her function, she still had left-sided weakness in her upper body. That weakness prevented her from shaking Dr. Kaiser’s hand to say thank you before leaving the hospital, but she promised him she would gather her strength and shake his hand someday.

That meant hard work ahead. During her stay in the rehabilitation center, Davis spent her days working hard on physical, occupational and speech therapy.

She started strong and kept getting stronger.

On her first day, she walked 50 feet with a walker.

“I was so thankful I could walk, and I just wanted to get up on my feet,” Davis said. “Then I realized that I could have lost that ability. It’s unbelievable that they were able to restore me to where I was.”

Although doctors thought Davis might need several weeks of rehabilitation, Davis was able to return to Tennessee after only five days of inpatient care.

One of Davis’ physical therapists said she recovered very quickly.

“It was impressive how high-level she’d become in such a short time,” said physical therapist Tim Koblenz.

“They were great,” Davis said of her rehabilitation therapists. “I felt like they were really on top of things, and they were very caring.”

Recovery after trauma and stroke: Davis regains strength and gratitude

Back home, Davis continued doing physical therapy to work on the issues with her left hand. She’s been doing well, staying active and exercising regularly.

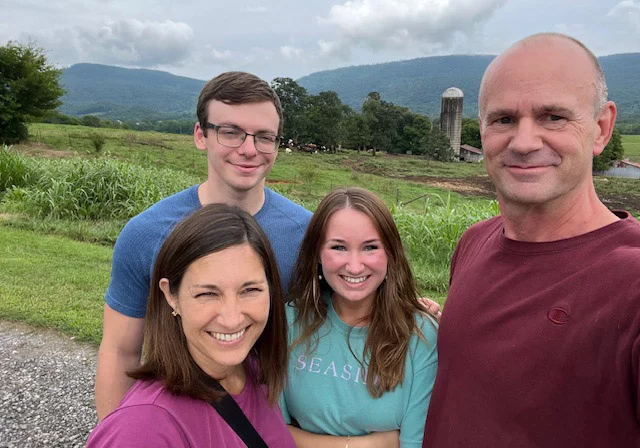

In September 2025, everyone involved in Davis’ case — from McLellan and the flight nurses, to Mitchell, Sachdeva and Koblenz — gathered to discuss Davis’ case as part of an educational presentation to promote continued teamwork across different entities involved in patients’ care. Emergency responders, Estes Valley Medical Center providers and pros at Medical Center of the Rockies shared their experiences and saluted one another for providing fast, top-notch care.

Thanks to excellent cooperation among medical pros in multiple northern Colorado communities, Davis walked away from a scary experience with her life — and the ability to say thank you in person.

“I just want to say thank you to every single person here for all that you did for me,” she said.

Then she walked over to Dr. Kaiser and shook his hand.