When Saren Peterson woke up from the first of two surgeries to remove a deadly and aggressive brain tumor, there were many reasons to be scared.

Were doctors able to take all the cancer out? What would her prognosis be, and what would treatments and recovery entail? Would she be able to return to college? What would her future be?

But like many 22-year-olds who love music, at the top of Saren’s list was the fear she might not recall the words to her favorite songs.

“I woke up from the surgery worrying that if some of my brain was gone, and something was missing, I would forget things. What if my family turned on music and I couldn’t remember the song?”

A few weeks later when she went to country artist Walker Hayes’ concert, she was overcome with relief and happiness.

“I was able to sing every single song that he performed and that was super awesome … like everything was still intact,” she said with a laugh. “I thought, ‘I still got it!’ I knew all the words, and that was a comfort. It made me realize that just because I’m sick, it doesn’t define who I am.

“I was very blessed that I came out of the operations with no issues, and that was a miracle.”

Saren’s doctors, family members and others frequently use the word “miracle” when they talk about her. The now almost 25-year-old maintains a positive mindset, celebrates milestones and stays motivated with grace, humor and poise that belies her age.

“Your body is already sick, and if your mind is negative, your body will follow, so sometimes the only thing you can control is your mind.”

Three years ago, Saren was diagnosed with an incurable malignant brain tumor called an astrocytoma, IDH-wildtype, WHO (World Health Organization) grade 4. These tumors occur when a type of glial cells, called astrocytes, which support nerves in the brain and spinal cord, grow out of control and become tumors.

Saren’s neurosurgeon, who performed two craniotomies to remove as much of the tumors as possible, was Dr. Krista Greenan at the UCHealth Memorial Hospital Central in Colorado Springs. She said astrocytomas fall under the same aggressive, malignant umbrella as glioblastoma, but include a mutation that makes them more receptive to surgery, radiation and chemotherapy.

“There is a lot to be learned about these kinds of tumors,” Greenan said. “It’s still a malignant brain tumor, but the fact Saren has survived three years is a great thing.”

Dr. Denise Damek, Saren’s neuro-oncologist neurologist at UCHealth University of Colorado Cancer Center at the Anschutz Medical Campus, agreed that Saren continues to defy the odds.

“At this point, given that it’s been three years, she would be heading into a long-term survivor kind of designation,” said Damek, also a professor of neurology at the University of Colorado School of Medicine. “She has already outlived the average life expectancy for this type of tumor.”

Like Saren, her family members make a deliberate decision each day to embrace a positive outlook as they contend with gloomy probabilities and dire statistics.

“It’s tough,” said her father, Randy Peterson, a U.S. Army aviator veteran and current Apache helicopter instructor with the National Guard. “As a parent, this is pretty rough news to get. While I am very pragmatic and want to know numbers, the fact that she is still with us is a miracle.”

Blurry vision and headaches prompt family to seek help for Saren

The oldest of four children, Saren was born in Provo, Utah and attended several schools across the country as her family moved with her father’s military career. When she was 9, they headed to Germany for seven years, then returned stateside to North Carolina for Saren’s last two years of high school.

By the summer of 2022, the family had returned to the western U.S., living in Peyton, a small town east of Colorado Springs where Randy was serving as an active-duty pilot at Fort Carson.

Saren, meanwhile, was a college student at Utah Valley University, getting ready to head back for her junior year after taking a year off to earn tuition money.

The future looked promising: She had an apartment lined up, several part-time campus jobs to consider and was inching closer to her degree in family science.

But those well-laid plans came to an abrupt and sudden halt in early July of that year.

Though Saren had never previously had vision problems, she began seeing black spots and blurry patches. She was plagued with horrible headaches, some lasting all day, and the left side of her face began freezing up.

Saren passed a neurological exam at the army base “with flying colors,” but was told to keep a diary and track any persistent symptoms.

A week later, she felt terrible.

“It hit me like a bus. My vision was blurry, and my head hurt. I was nauseous, and my face was paralyzed. It was the whole nine yards.

“I had never broken a bone or taken much medication or been truly sick. The only time I had ever been under was getting my wisdom teeth taken out. So, when these things all came together, I thought … there must be something really wrong with me. It seemed like cancer was the only reason that could explain everything.”

Saren’s mom rushed her to the army base ER where a CT scan confirmed her premonition.

“The doctor said, ‘You’ve got a large mass in the right side of your head … You need help, and you need to be transferred.’

“It was really hard, as I knew my life was going to change forever. I would not be able to return to school and be an adult; instead, I’d be dependent upon my parents. I was processing my heart being broken.”

Saren goes in for neurosurgery, and doctors make a grim discovery

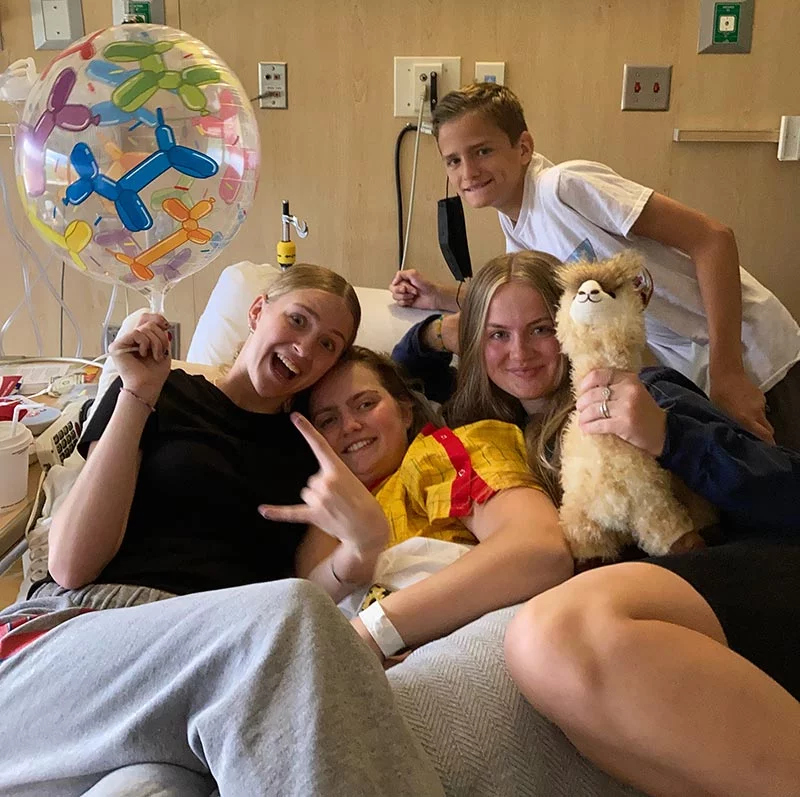

At Memorial Hospital Central in Colorado Springs, Saren’s family rallied around her, first in the ER, and then in the room where her team was caring for her after completing new brain scans.

It was then that Saren and her family met Greenan, who would become an integral part of her care team.

“I felt like I was always part of the conversation of them going inside my head. I was hoping, as naïve as I was: ‘Let’s get this out of me. Hopefully, it’s not cancerous, and I can get on with my life.’ That’s what I wanted, but that didn’t happen.”

Brain imaging showed a large mass on the right side of Saren’s brain. It’s what’s known as “partially enhancing” and “partially cystic.” Grennan performed a craniotomy and was able to remove the enhancing component that she had spotted on the scan.

Saren and her family hoped that the pathology results of the remaining mass would indicate it could be successfully treated with chemo and radiation so she could avoid a second operation.

In the meantime, she was out of the hospital within 24 hours with no side effects from the surgery other than a stitched wound from ear to ear.

Saren left the hospital with her hair in braids courtesy of Greenan, who had taken the time to wash and fix Saren’s hair so that cleaning the wound would be easier.

When the tumor results came back, the news was devastating. Saren had an aggressive grade 4 glioma called an astrocytoma IDH-mutant.

But there was a glimmer of hope that her family clung to. That mutation in the genetic makeup of the tumor improved Saren’s odds, making it more responsive to treatment. The mass hovered in the right frontal lobe of her brain, making it more accessible for surgical removal.

A team of multidisciplinary brain tumor experts reviewed Saren’s case at the University of Colorado Hospital and mapped out the next steps to give her the best possible outcome. That meant a second surgery to remove as much of the malignant tumor as possible.

“I remember talking to my mom and being sad and frustrated,” Saren said. “The surgical site had healed. My body had healed, and I had to face it again and have them re-open me. I thought, ‘I just went through this, and now I have to do it again.’”

Saren faces a second risky surgery and a wound infection

Six weeks later, in August of 2022, Saren prepared for her second brain surgery. She knew Greenan wanted to be as aggressive as possible. But there were risks involved. The tumor hovered in right side of her brain, which controls functions on the opposite side of the body.

She faced the possibility of partial paralysis on her left side or needing physical and occupational therapy afterward – which would be especially challenging for her since she happens to be left-handed.

But when she woke up from surgery, Greenan had good news: She was able to remove 90% of the tumor, and what was left would be treated with a combination of radiation and chemo.

During the surgery, Greenan used a variety of multi-modality techniques such as ultrasound, dyes and navigation software to ensure that only the tumor was removed and not any brain tissue that would impair Saren’s mobility or ability.

“They did tests to see how the left side of my body reacted, and I had no issues. It was such a relief. There were no complications. Dr. Greenan did a fantastic job.”

As with the first surgery, Saren was able to leave the hospital a day after her surgery. Her caregivers instructed her to “Live, walk, hang out with friends, and be with loved ones.”

Before the next phase of her treatment could begin, Saren had to deal with a severe staph infection at the wound site that brought her back to the hospital for a week to control it. Physicians completed a “wash out,” or intense clean-up of her skull to eliminate all of the infection, and she would be on intravenous antibiotics for six weeks.

Saren endures 14 months of aggressive treatment to fight a malignant brain tumor

As Saren was completing that phase of her health battle, she embarked on six weeks of daily radiation and chemotherapy followed by a year of oral chemotherapy. The regimen left her exhausted, as she struggled to take classes online while living at her family home. Finally, in fall 2023, her chemo treatments ended, though she acknowledged the moment brought her some anxiety.

“I was happy getting off of it, but I was also terrified that not being on chemo might mean my cancer was going to grow back.”

The one-two radiation-chemo punch, along with the surgery, meant that doctors had removed nearly all of Saren’s tumor. The remaining mass is currently dormant. It hasn’t shrunk, nor has it grown, and Saren being a glass half-full type of person, sees the positive side of her condition.

“I won’t be able to ring the bell that I am officially ‘cancer free’, but I am living my life like I am, and it has not inhibited me from living like I did before.”

Damek, Saren’s neuro-oncologist, said when it comes to a grade 4 brain glioma, specialists don’t talk about “remission” as with other types of cancers. But she is encouraged that her scans have been stable with “no evidence of new tumor activity growth.”

Greenan agreed.

“She’s got no evidence of disease progression right now, and that’s fantastic.”

Malignant brain tumor survivor chooses hope — and a future in social work — in honor of other patients

Saren continued to complete her degree online and traveled in person to her May 2025 Utah Valley University graduation, where she walked across the stage to the cheers of family and friends.

“There were a lot of thankful tears when she got that diploma,” her father, Randy, said. “It was very, very good that she got to that moment, and very emotional.”

Last fall, Randy put his helicopter skills and expertise toward a new job as an air ambulance pilot serving UCHealth facilities. A civilian pilot before joining the Army at 32, he spent over 15 years in active duty and had five overseas deployments in the Middle East.

While he took a military leave of absence from the air ambulance position to return to the National Guard as an Apache helicopter trainer, he looks forward to working in the future on air ambulances so he can once again transport patients, like his daughter, to UCHealth hospitals.

“I was proud to fly that helicopter,” he said. “It was a really positive experience.”

Saren, nearing her 25th birthday, works full-time managing a local health club and plans to pursue a master’s degree in social work. She’s eager to help others who are going through difficult times.

Speaking from experience, she wants people to know, “It’s OK not to feel OK.”

“I have been to a place where I hit rock bottom. So, for me, being able to go to therapy and have coping skills are things I went to help others with.”

Saren has regular checkups with Damek and undergoes quarterly MRIs – a task she hopes will one day become an infrequent inconvenience as opposed to a routine part of her life.

“Those MRI and oncology meetings are stressful, but what else can you do?” her father said. “You have no other option. You just start to appreciate every day.”

Saren is determined not to let cancer discourage her from attending graduate school and other exciting future opportunities. She is determined to fight both for herself and for other patients who have not had her same outcome.

“The way I look at it, I am alive when people with my diagnosis are not and don’t have the chance that I do. Sure, there were rough times, but I know if I live a week, 12 months, 10 years, or die when I am 80, I am alive for a reason. And I am fighting for that reason.”