It was the first week of April, about two months after the first reported novel coronavirus case in the United States, when Dr. Ernest Moore and his colleagues began reviewing the first autopsy reports of patients who had died from the disease in China. One finding in particular caught their attention.

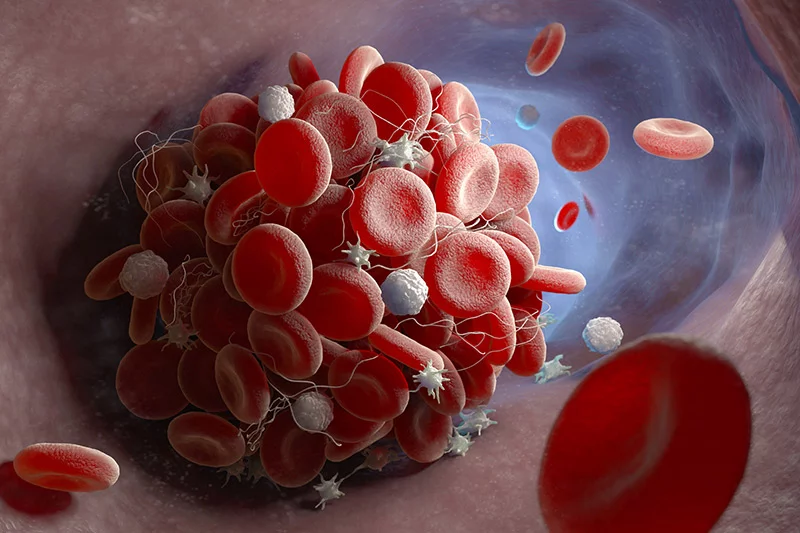

The patients’ ravaged lungs showed blood clots in the large and small blood vessels and alveoli, or air sacs. Over the next several weeks, autopsies from patients killed by COVID-19, the disease caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus, in Italy, Brazil, Germany and New Orleans revealed the same pattern.

“They were incredibly consistent,” said Moore, distinguished professor of GI, Trauma and Endocrine Surgery at the University of Colorado School of Medicine and longtime trauma surgeon at Denver Health. The COVID-19 victims had succumbed to acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), a condition in which the alveoli fill with fluid and fibrin, the fibrous protein that forms blood clots. The combination chokes the flow of oxygen to the body.

The formation of blood clots in COVID-19 patients wasn’t the major revelation of the autopsies, Moore said. Studies of the link between advanced ARDS and blood clots in the lungs go back to the early 1980s. The key point was that COVID-19 patients appeared to be especially vulnerable to rapid, aggressive coagulation and clotting.

“These patients are at even higher risk because of their phenomenal hypercoagulability,” Moore said. COVID-19 also appeared to suppress their bodies’ ability to perform fibrinolysis, the process of breaking down fibrin, Moore added.

Blood clots in COVID-19 patients

The autopsy reviews helped to support an FDA-approved trial now underway at five institutions, including Denver Health and UCHealth University of Colorado Hospital on the Anschutz Medical Campus. The randomized trial tests the effectiveness of administering intravenous doses of tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) to break up the deadly blood clots in the lungs of COVID-19 patients battling ARDS, thereby improving gas exchange and blood flow. The medication is already FDA-approved to dissolve clots that block blood flow to the brain, heart and lungs.

Patients who have been ventilated more than 10 days are excluded. A control group will not get tPA but will receive standard treatment for ARDS.

Moore, Dr. Robert McIntyre, the principal investigator for UCH and professor and chair of GI, Trauma and Endocrine Surgery at CU, and researchers at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston – also part of the trial, along with National Jewish Health in Denver and Long Island Jewish Hospital in New York – collaborated on the research leading to the trial and made their case for it in a late March edition of the Journal of Acute Care Trauma and Surgery.

Moore, McIntyre and colleagues at Denver Health and UCH also published the results of a study of 44 COVID-19 ICU patients in the May 2020 issue of the Journal of the American College of Surgeons. The study demonstrated that in a majority of patients, fibrinolysis shutdown, increasing the risk of blood clots forming.

Old idea for a new disease

The idea of using clot-busting medications to attack blood clots in ARDS patients isn’t new. A 2001 Phase I clinical trial concluded that they could safely treat patients who failed to respond to mechanical ventilation. Moore noted that a number of subsequent animal trials also produced favorable results. Its approval for this purpose stalled because of the potential risk of bleeding, Moore added.

“We didn’t seem to have a need for it, considering the risk,” he said. But the COVID-19 onslaught changed the equation, with so many seriously ill patients enduring extended periods on ventilators and ECMO (extracorporeal membrane oxygenation) machines, both of which carry substantial risk for the patients who survive them.

“The risk of tPA is small compared to ECMO,” Moore said. “And the longer patients are on ventilators, the greater the risk of a catastrophe occurring.”

Another factor driving the trial was concern for conserving resources for patients and hospitals, McIntyre said.

“We wondered could we give [tPA] to people who needed to be put on ventilators but the hospital didn’t have a ventilator,” McIntyre said. “There might also be patients who needed to be put on ECMO with no ECMO machine available. Could we improve their condition without having to put them on ECMO?” The medication might also help to shorten patients’ time on ventilators, he added.

Delayed launch

The timeline of the study, however, illustrates the difficulties of launching investigations in the midst of a pandemic. The FDA and hospitals were swamped with study proposals, Moore said, which inevitably led to approval delays. The idea for the tPA study actually came on March 14, when Moore and his son, Dr. Hunter Moore, a transplant fellow at UCH, were in Steamboat Springs, stymied from skiing because of COVID-19.

They contacted previous research colleagues at Beth Israel Deaconess and composed a proposal for the Journal of Acute Trauma and Surgery article, published about a week later. Moore said the article drew interest from the National Institutes of Health and the Department of Defense, but neither offered funding. Genentech, the manufacturer of Alteplase, the tPA medication administered to study enrollees, ultimately funded it.

The study group submitted the trial to the FDA for approval in early April, when worries abounded that the surge of COVID-19 patients would swamp supplies of mechanical breathing devices. That was an especially acute fear in New York, at that time the epicenter of the pandemic in the United States. However, a host of federal and hospital regulatory and financial challenges delayed the start of the trial until mid-May, Moore said.

Containment success, enrollment challenges

Since the time of the launch, the pressure on the hospitals involved in the study has lessened considerably, thanks in large part to determined efforts by their states to contain the virus. Ironically, that success, coupled with the relatively slow launch, created a trial enrollment problem: the target is 60 patients, but only three had been recruited by early July because the pool of qualifying patients has shrunk.

No one wants another surge in New York, Massachusetts or Colorado, of course. But many patients now fill hospitals in COVID-19 infection hotbeds, notably Florida, Texas, Arizona and California. That spurred Moore to contact Genentech, which invited the trial team to consider additional medical centers in Miami, Tampa, Phoenix, Houston and San Diego as recruitment sources.

Moore said in early July that Scripps Health in San Diego, Jackson Memorial Hospital in Miami and St. Mary’s Medical Center in West Palm Beach, Florida have said they are “eager to start” the trial, while hospitals in Houston and Phoenix are discussing the feasibility of conducting the study in their centers, he added.

In addition to the still-meager number of trial enrollees, a handful of hospitals have in recent months used tPA “off-label” to treat small numbers of COVID-19 patients with ARDS and published the results in “case series” reports. These include hospitals in Boston, New York, Georgia and India. Moore, McIntyre and colleagues in Denver, Boston and New York also published a case series in April, shortly before the trial launched. The hospitals report some success with the treatment, but all of them emphasize their observations are anecdotal and lack the rigor of a randomized trial.

tPA is not a standalone solution

The use of tPA is just one piece of a still-shifting strategy to contain a COVID-19 assault that shows no sign of relenting. The rapidity of the disease attack and the lack of data about the virus forced hospitals to take a “shotgun approach” to treatment in the early days, McIntyre said. Multiple clinical trials of anti-virals (remdesivir, hydroxychloroquine), anti-inflammatories (dexamethasone, sarilumab) and convalescent plasma quickly launched at UCHealth and elsewhere.

“Many patients got all of these treatments,” McIntyre said. “As time has gone on, with our own experience, as well as reports from around the world, we’ve started to develop more of a focused strategy.”

For example, convalescent plasma is a treatment mainstay at UCHealth, while the once-hyped hydroxychloroquine is no longer part of the mix (despite determined boosting by the Trump administration) due to a combination of weakly supported success and documented evidence of risk. Providers continue to refine their use of remdesivir and dexamethasone and gather data about their effectiveness, McIntyre added.

“The pace of publication and scientific discovery is still very rapid,” he said. “We have to evaluate these treatments with an eye toward being critical.”

Multi-front attack

COVID-19 also attacks patients on more than one front, presenting yet another challenge. Moore said the disease advances in three phases. The first is the viral infection that hijacks the DNA of its victims’ cells and invades the body. That triggers an inflammatory response that in turn promotes the blood clotting in the lungs that can in the worst cases lead to ARDS.

“So it makes sense to attack the disease at multiple branch points,” Moore said. For that reason, “our study doesn’t prohibit enrollment in any other study,” he added

But McIntyre noted that while a multi-front approach may prove to be effective and the best chance to save lives, it also complicates evaluating new treatments and drawing hard conclusions from them.

“The difficulty when we’re giving multiple therapies is that it’s hard to know if they are or are not working, and if they are, which one is it,” he said. The situation increases the importance for researchers to design their studies carefully, which is challenging enough in ordinary times, let alone a world consumed with stopping as quickly as possible a virus laying waste to so many lives.

Moore emphasized that whatever the outcome of the tPA trial, its foundation is solid, the product of long years of research at the CU School of Medicine into the physiology of lung function and disease that preceded it.

“The autopsies of COVID-19 patients piqued our interest because of the similarities to our previous findings with ARDS,” he said. “It underscores why we, as surgeons, need to continue to conduct basic science research to prepare us to propose novel therapies based on science and apply it to the appropriate patients.”