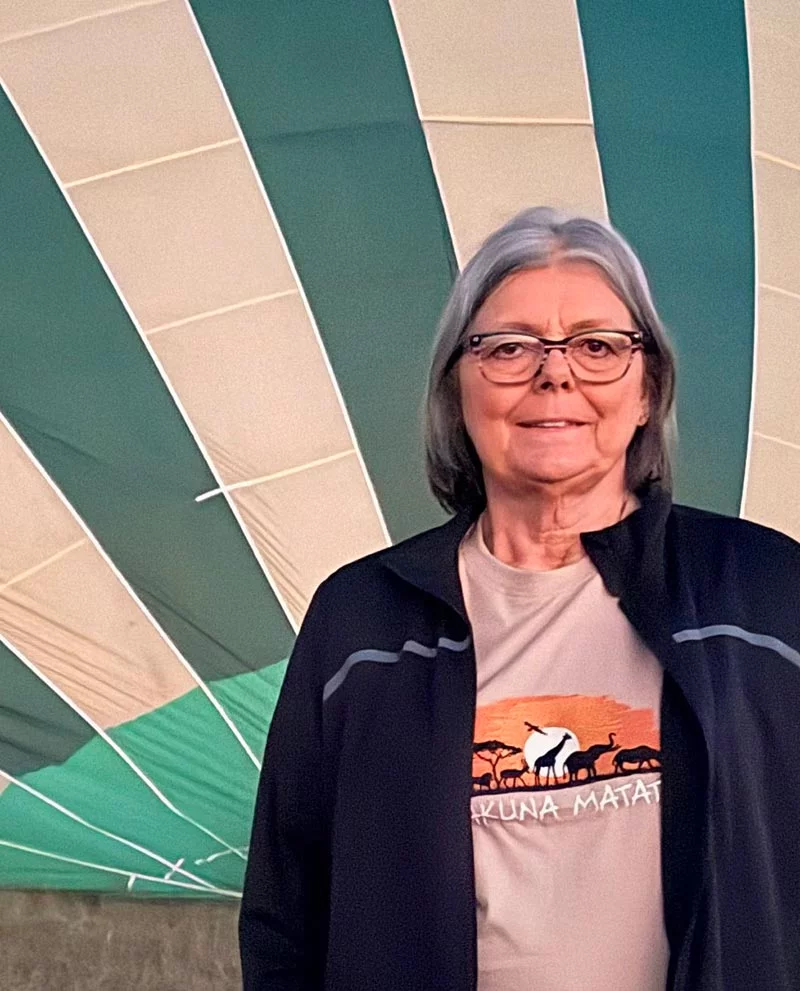

At sunrise on a recent June morning, Val Frank stepped into a hot-air balloon and rose over the flat, wildlife-dotted east African terrain of Masai Mara National Reserve in Kenya. She was thousands of miles from her home in Sterling, Colorado, but in a sense, she was even farther from the life she’d lived only about a year and a half earlier.

In early December 2023, Frank was awaiting a liver transplant. Her original organ was stiff and scarred, the result of cirrhosis that began with a buildup of fat in her liver cells and silently progressed over the years. Because of the disease, she was constantly fatigued, craved sleep and battled periodic bouts of encephalopathy, which made it difficult to think. Her complexion faded to a color that her daughter Jessie described as “almost gray.”

That all changed on December 13, 2023, when Frank got a liver transplant at UCHealth University of Colorado Hospital. Freed from the grip of her liver disease, she began reclaiming her life. An ascent from the Kenyan veldt as the day dawned seemed a perfect metaphor for her return to health, but it probably wouldn’t have happened without plenty of help from those on the ground.

There was her family: her husband, three children and nine grandchildren. There were her coworkers at the laundromat in Sterling, where she has worked for the past eight years. There was her primary care physician at Northeast Colorado Family Medicine Associates, who persisted in finding an answer to Val’s declining health.

There was the UCHealth transplant team that directed the transplant process before, during and after the surgery. But before getting her new liver, Frank benefited from the collaborative care of Dr. Amanda Wieland and Dr. Thomas Jensen, associate professors of Medicine-Gastroenterology and Endocrinology/Metabolism/Diabetes, respectively, at the University of Colorado School of Medicine on the Anschutz Medical Campus.

A team approach to treating metabolic liver disease

Wieland and Jensen co-direct the MASLD Multidisciplinary Clinic — named for metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD), formerly called nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. The two treat patients with MASLD, as well as those whose condition has progressed to a more serious stage called metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH), formerly called nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. MASH inflames the liver and may cause fibrosis, or scarring. They also work to manage the health of people like Frank, whose cirrhosis causes liver scarring and irreversible damage that may require a transplant and can lead to cancer.

Frank, referred to and diagnosed by Wieland eight years ago, is one of millions of people in the United States whose excess liver fat led to disease not caused by alcohol use. An estimated one-third of people in the country (86 million) have MASLD. For those with MASH, the estimate is 15 million. Both numbers are on a steep rise, and the American Liver Foundation pegs MASH as a top cause of liver transplants in the country.

“Right now, fatty liver disease will probably become the No. 1 indication for liver transplant,” Jensen said.

One of the main causes for this surge is Type 2 diabetes, which is often a companion of MASLD because it interferes with the liver’s regulation of blood sugar.

The American Diabetes Association estimates that 70% of people with Type 2 diabetes also have MASLD. Recognizing that, Jensen helps patients like Frank manage their disease with close attention to diet, weight, blood pressure and cholesterol control and medications. Frank learned she had Type 2 diabetes about 20 years ago, and all of her efforts to be as healthy as possible help prevent liver disease from worsening. Meanwhile, Wieland concentrates on treating the disease according to its stage of progression.

A new medication leads to a pivot in care for MASH

Wieland noted that the clinic has recently turned its attention to seeing more patients at high risk for MASH and post-transplant patients whose MASH has recurred. An important reason for that is the FDA’s approval in March 2024 of the first and so far only drug to treat MASH.

The drug, resmetirom (brand name Rezzdifra), gives the clinic a new tool to help patients with stage 2 to 3 fibrosis of the liver stave off cirrhosis, Wieland said. The hope is that “if you add that medication in, you can stop that progression or even reverse it.”

Providers at the clinic also care for patients after they have had liver transplants.

“The risk for metabolic disease doesn’t go away” with transplant, Wieland said.

Resmetirom and new drugs now in the pipeline might help treat patients who still have MASH after their transplants, but that’s a nuanced decision because resmetirom was not studied in transplant patients, Wieland said.

“We’re trying to figure out if the new meds are things that we should use in our post-transplant patients proactively,” she said.

Some post-transplant patients may see the MASH they previously had recur, while others experience it for the first time after the surgery, Jensen added. The reasons aren’t fully understood, but the disease could be caused by the anti-rejection drugs transplant patients must take, a transplanted liver that had excess fat to begin with, or insulin resistance caused by diabetes, he said.

Jensen said he also may incorporate diabetes medications, particularly GLP-1 receptor agonists – think Ozempic, Trulicity and Mounjaro – that research has shown work well in decreasing liver fat and fibrosis. In another recent study, these drugs showed promise in slowing the progression of MASLD in patients who also had diabetes.

For Wieland’s part, she said that these drugs are not yet approved to treat liver disease specifically, but she anticipates that happening within the next year, if not sooner.

Alcohol use creates a hybrid disease foe

As a further complication, Jensen pointed to a relatively new entity, metabolic and alcohol-associated liver disease (MetALD), a condition in which a person’s alcohol consumption contributes to worsening their MASLD. A PEth test, which detects the presence of a biomarker that is an indicator of chronic alcohol consumption, is used to decide whether a person has MASLD with no alcohol involvement or MetALD (the combination of metabolic disease with alcohol use).

One recent study concluded that MetALD increases the risk of MASH, liver fibrosis and liver cancer. “It’s like adding kerosene to the fire of MASLD,” Jensen said. For a provider, MetALD creates the double problem of trying to manage patients’ metabolic conditions, like diabetes and obesity, as well as their alcohol consumption, for which there are limited medication options, Jensen said. He noted some research that suggests GLP-1 drugs could decrease alcohol craving, but the data is limited.

Developing directions in liver disease treatment

Meanwhile, the search for new ways to treat metabolic liver disease continues. Wieland said that one important area of research focuses on combination therapies that work together to arrest or reverse liver inflammation and fibrosis.

Clinicians might fine-tune the combination therapy, based on the degree of inflammation or fibrosis affecting a patient’s liver, she added.

Researchers are also exploring the genetic roots of liver disease and building their understanding of the biology that drives it. That’s the mission of the Colorado Center for Personalized Medicine, which houses the biobank, a large repository of deidentified DNA samples, extracted from the blood and saliva of donors. This reservoir of DNA data is available for study of disease and many other uses.

“If we could identify at a genetic level the risk and understand the disease mechanism, and could develop targeted therapies based on that, that would be ideal,” Wieland said.

It’s obviously important to find treatments for the most seriously ill patients, but Wieland emphasized that it’s equally important to prevent people from reaching that stage in the first place.

“A big unmet need is making sure we are not missing people that have at-risk fibrosis,” Wieland said. “How best to identify those people is very challenging.”

The solution might be better blood tests or algorithms that help providers more precisely classify the stages of their patients’ disease, Wieland said. That would drive better decisions about the level of treatment each patient needs.

An overarching problem in fighting metabolic liver disease is the staggering number of people in the United States with Type 2 diabetes, as well as those with prediabetes and insulin resistance.

“If we got a really amazing handle on managing Type 2 diabetes,” Jensen said, “would we see a reduction in the number of patients with more advanced liver disease? Certainly, because Type 2 diabetes is the No. 1 risk factor.”

A belated diagnosis carries a heavy cost

Val Frank’s case highlights both the complexity of metabolic liver disease and also the importance of Jensen’s and Wieland’s multidisciplinary management of it. Genetics may have played a role: her father died of liver disease. She has Type 2 diabetes that she attempted to manage with medications, but her liver disease went undiagnosed for more than a decade before she saw Wieland. At that point it had progressed to cirrhosis and put Frank on an inevitable path to transplant.

She might not have gotten to a transplant without her primary care physician in Sterling. He had ordered a liver biopsy that didn’t reveal disease, but batteries of blood labs over a period of years afterward continued to worsen, even as she got no answers for what was wrong.

Her physician wasn’t ready to give up. “He finally said, ‘Do me one more favor. Go to UCHealth,’” Frank recalled.

Managing the disease before the transplant

She followed his advice and saw Wieland, who did another liver biopsy that showed the buildup of liver fat cells and scarring of cirrhosis. Wieland explained the disease and made clear to Frank the consequences of the cirrhosis.

“She said it is going to progress, and when your lab numbers are right, you are going to get a transplant,” Frank said. “I said, ‘We’ll do what we got to do and pursue what we have to pursue.’”

With that, she began making the two-hour drive to UCHealth every six months to see Wieland and Jensen. Wieland managed Frank’s long list of medications and monitored her blood labs, while Jensen helped her control her Type 2 diabetes with medications. She also cut out soda completely and tried to eat more fruit and salads and get in some walking and light exercise. The goal was to live without the transplant as long as possible.

There were bumps along the way, most notably the encephalopathy that clouded her mind and tossed her words into salad. At a breaking point one day she was rendered incapable of operating her phone and the TV remote.

“She wasn’t making sense. She didn’t know if she had taken her medications that morning or night,” Jessie remembered. The encephalopathy landed her in the emergency room and overnight in the hospital. Wieland prescribed medications to manage it.

The transplant and aftermath

Frank got on the liver transplant wait list Nov. 21, 2023, but had to clear another hurdle before getting there. The extensive testing required by the transplant team at UCHealth revealed a blockage in her heart that had to be repaired with two stents before approval.

But her luck improved after that. Cleared for transplant, she placed number two on the organ wait list. On December 12, she was driving home from work at 5 p.m. when her phone rang. The voice on the other end said the magic words: “Mrs. Frank, I believe I have a donor for you.”

The next day, she was in surgery at UCH with Dr. James Pomposelli, who completed the transplant remarkably quickly, Jessie said.

“They took her back, and my dad, brother and I went to dinner,” she recalled. “We had barely ordered, and they said, ‘She’s done and in recovery’.”

Another surprise followed. A transplant patient normally goes to the ICU after surgery, but Frank instead went to a medical-surgical floor at UCH for recovery and was discharged from the hospital a mere 52 hours later, rather than the typical one to two weeks.

“That liver was mine,” Frank said.

The road back to a new life

She doesn’t minimize the challenges of recovery. There were and are many anti-rejection medications to manage, and she still makes the long drive to UCHealth facilities in either Fort Collins or Greeley to have her labs checked every four weeks. She’s gotten back to work at the laundromat, but Jessie said the transplant slowed life in general down for a period.

“It was hard for her to take it easy at first,” she said.

Today she is intent to make the most of the improved health her new liver has given her. She loves attending her grandsons’ baseball games and taking opportunities to travel. In addition to the journey to Kenya, she’s traveled to east Texas to see son Jordan.

“If there is a vehicle leaving Sterling, she is in it,” Jessie said jokingly.

Frank credits Wieland and Jensen for helping her reach this new stage of her life.

“I can’t say enough about them,” she said. “The two of them have an amazing relationship. I love that they work together. Dr. Wieland is one amazing doctor. Dr. Jensen is a book of knowledge.”

Back on earth after the thrill of floating over Kenya and traversing its grasslands on a safari, Frank is intent on finding more of what the world has to offer after her disease did so much to confine her. She also recognizes that she owes her life to her donor and emphasizes the importance of that person and all others who make that sacrifice on behalf of others.

“I look at life differently,” she said. “I wasn’t given this gift for nothing. I’m not going to lie around and not enjoy life.”