Abbey Lara still remembers picking cotton as a child and feeling the scratchy plants poking her legs as she stuffed them in a burlap sack.

Her grandmother, Abigail, for whom she was named, lived on a plantation near Mexicali in northern Mexico. Mama Gai, as they called her (short for Mama Abigail) paid her rent by tending fields of cotton and wheat. When Abbey, her sister and their parents went to visit, they worked too.

“Child labor? Sure. That’s what Mexican families do when they’re poor,” said Lara.

Both of Lara’s parents came from extreme poverty.

Her dad, José, was one of 16 children who grew up in a small town in central México called El Espejo, which translates in English to “the mirror.” He never finished kindergarten and later came to the U.S. to work as a migrant apple picker through the Bracero Program, which brought Mexican laborers to the U.S.

Lara’s mother was born in the western Mexican region of Michoacán, known for its stunning coasts and colonial cathedrals. One of five children, she, too, barely got to go to school. Maria Alicia later met her husband in Tijuana. He was already living and working in the U.S. They dated for about a year, then Lara’s mom married her dad and the couple moved to a rural area northeast of San Diego where they raised their two daughters.

“We grew up on a mountain,” Lara said. “We had a big garden in our backyard. We had apple trees. My dad was a hunter. He taught me to use BB guns. We had chickens too.”

Lara loved the neighbor’s dog, Muddy. But Muddy loved the chickens, and when Muddy attacked one of them, Lara calmly ran inside, grabbed a needle and thread and did her best to stitch up the chickens’ wounds. To her, it was no big deal.

“I used to watch a lot of nature shows.”

But others marveled that she wasn’t the least bit squeamish, and instead, was fascinated by the chickens’ anatomy.

“That’s when my family knew I was going to be a doctor someday,” Lara said.

Despite having no family members who ever had gone to college, much less graduate school, Lara did make it to medical school and beyond.

On the day when she graduated from medical school at the University of California San Diego — where she also earned her undergraduate degree — Lara’s parents beamed with pride.

“My dad was a man of few words,” Lara said, tearing up as she thinks about her father, who passed away in 2008. “At the graduation dinner, he looked at me and said, ‘You are Dr. Lara. You will always be Dr. Lara.”

Indeed.

Dr. Abbey Lara is now a pulmonologist and a critical care doctor at UCHealth University of Colorado Hospital. She is also UCHealth’s medical director for health equity and an associate professor at the University of Colorado School of Medicine on the Anschutz Medical Campus. Lara holds the Marsico Chair for Excellence, an endowment that gives her the freedom to support young doctors and researchers who are expanding knowledge of lung and breathing problems.

As Lara reflects of her rise from those cotton fields to the halls of higher education and her leadership roles at a top academic medical center, she is proud and grateful.

“I am, quite literally, the picture of the American Dream.”

Throughout the pandemic, Lara has played a key role in caring for critically ill patients in COVID-19 intensive care units (ICUs). During the spring of 2020, when doctors and nurses had little knowledge about the new coronavirus and few therapies to treat sick patients, Lara and her colleagues had to march in fearlessly and do their best to keep patients alive. Each day, when Lara studied the people in her care, she couldn’t help but notice that a disproportionate number of them were Black or Hispanic people — including workers who had the kind of jobs that didn’t allow them to isolate at home.

“It was striking how many of my patients could have been members of my own family,” Lara said.

Her compassion for people from all backgrounds makes Lara uniquely sensitive and talented at her job.

“She’s a remarkable human being,” said Dr. Rita Lee, a friend and UCHealth colleague, who was Lara’s chief resident back when the women were training at the Cleveland Clinic in the early 2000s.

“I was with her the first time a patient passed away,” Lee said. “It was so emotional and challenging. It was really touching to see how deeply she cared for her patients.”

“She’s always thinking about other people and what their perspectives might be.”

Central to Lara’s life and work are her Mexican roots and humble upbringing.

On a California mountain, a little girl’s dream took shape

Apples and economic opportunity brought Lara’s dad to California at age 19. Then help from a kind boss led him to a new career and a giant mirror, a fateful twist for a young man from El Espejo.

Lara’s dad was working at an orchard on Palomar Mountain.

“The owner was Doris Bailey. She took a liking to my dad and said, ‘You’re so bright and good with your hands. You can’t be working in the fields.’”

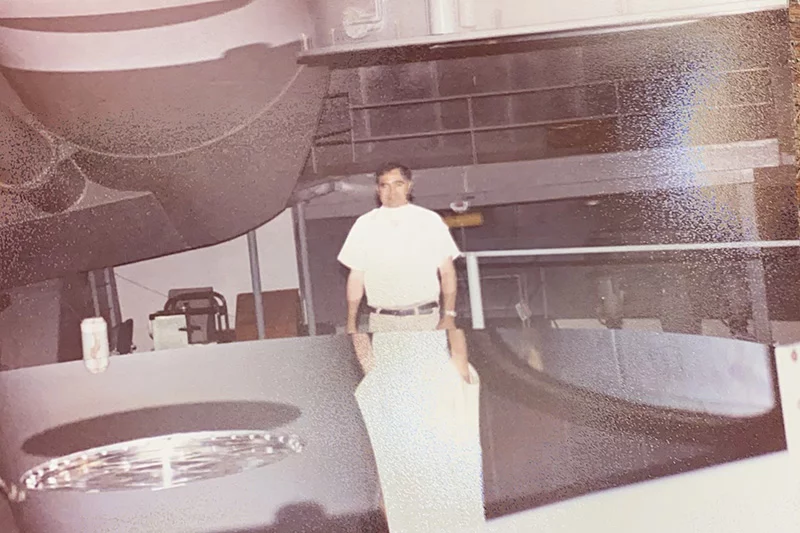

Bailey introduced José to the managers of Caltech’s famous Palomar Observatory located on the summit of the mountain. It boasted the 200-inch Hale Telescope, once the world’s largest and most powerful.

José became a maintenance manager at the facility and was the single person trusted to hand-wash the expensive, giant mirror that powered the telescope and made space exploration possible.

“It was such a source of pride that this person who had no education was trusted with this job,” Lara said.

A Swedish coworker also took José under his wing and taught him English. As a result, Lara’s dad spoke his adopted language with a funny lilt.

“He always spoke English with a Swedish accent,” Lara said.

Her mom spoke only Spanish when she arrived in the U.S., but learned English over time and insisted that her girls assimilate.

Fearlessness and a powerful family work ethic

Abbey was always fearless, said her mom, Maria, who is now 74.

She’d carry around dead snakes and mice. Sometimes, she’d dissect them.

“We’re going to see the heart,” she’d excitedly tell her mom.

Life was good on Palomar Mountain.

“It was a very pretty place to live, but lonesome sometimes too,” Maria said.

Almost no one spoke Spanish, so Maria tried to learn English and took on extra work to help support the family.

“I wanted to improve, to show I could do something. I started embroidering,” Maria said.

She made and sold sweaters, worked as a cook in a monastery. She later earned her GED and a certification as a home health aide.

A local family doctor inspired Lara’s dreams

Along with her family, a rural doctor had a profound influence on Lara.

“The family physician who took care of our entire family was an amazing person. Dr. Warren Jacobs loved being a doctor. And he was the whole reason that I wanted to go into family medicine,” Lara said.

Between stitching up chickens and finding a mentor in her community, Lara made an early prediction about her career.

“I was about 6 or 7 and we were driving near La Jolla,” Lara said.

She spied the buildings at University of California San Diego (UCSD) and made a bold pronouncement from the back seat of the car.

“I’m going to go there for college. I want to be a doctor.”

Her parents supported her ambitions by moving Lara at age 12 from a small school on Palomar Mountain to larger middle and high schools in Escondido near San Diego. There, Lara had more opportunities, excelled in academics and played basketball and softball.

Lara’s older sister, Lucy, sometimes helped her with homework. Teachers stepped up too.

Having barely gone to school themselves, Lara’s parents couldn’t help much with academics, but placed great value on the girls’ achievements.

Maria remembers taking Abbey’s report card to school and asking teachers if her daughter was taking the right classes to make it to college and beyond.

“We didn’t have any education at all. My mother never could write a single letter,” Maria, said, tearing up as she recalled the family’s struggles.

“We always encouraged the girls to learn. We didn’t want it to be hard for them like it was for us.”

Lara’s childhood dreams became a reality when she got in to UCSD. To save money, she commuted to campus. She majored in microbiology and psychology with dual minors in neuroscience and philosophy.

There were times when Lara doubted she’d get in to medical school. When worries overwhelmed her, her parents gave her a great gift.

“I was questioning my potential and ability and they said, ‘So, what’s the worst thing that’s going to happen if you don’t’ get in? You’ll still be our daughter.’ They decreased the pressure I was putting on myself and made it OK,” Lara said.

Her parents’ approach was simple and sweet: “They gave us lots and lots of love.”

Of course, Lara did get in to medical school. When she graduated, her mom shared the news with their old family doctor. By then Jacobs was retired, but he proudly saluted Lara. He had never forgotten the little girl with big eyes and dark black pigtails who always told him she’d be following in his footsteps.

A talent for being the calmest person in the room

Along with family medicine, Lara also explored specialties, including cardiology and infectious diseases. She found role models among intense, dedicated women.

“I wanted to be just like them, taking care of complex patients,” Lara said.

She ultimately found her calling in pulmonary and critical care medicine. Her personality was a perfect match for high-stress environments.

“You have to be able to calm the waters,” Lara said.

She loved ICUs, where nurses and doctors team up.

Of course, she never imagined she’d have to put her skills to work during the worst global pandemic in more than a century.

“Medicine is a stressful career. But I’m good at being the calmest one in the room and leading a team,” she said. “At the end of the day, what matters most is the patients. They have to put their trust in complete strangers.”

Of course Lara had to communicate with many relatives whose loved ones died of COVID-19.

Thankfully, she had learned years earlier how to provide solace.

Back when Dr. Lee was her chief resident in Cleveland, Lara remembers feeling utterly powerless when she coped for the first time with a patient who died.

“I don’t know what to do,” Lara told Lee.

“This is what we do. We stay here with the patient and the family,” Lee told her.

“Working in the ICU is an adrenaline rush,” Lara said. “I also realized that one of the most important aspects of the job is sharing my emotions and supporting patients in having a dignified death.”

She’s quick to shed tears with patients and family members alike. Perhaps these experiences prepared her to deal with her own family’s sorrows a few years later.

A sad personal lesson on the care all patients deserve

Lara was a young doctor doing her fellowship in Denver in 2008 when she received a call that her dad had cancer.

The news was utterly heartbreaking. Lara instantly rushed home to help.

While her dad was hospitalized, his doctor refused to speak with Lara.

“The experience of my father’s doctor refusing to speak to me was both traumatizing and educational as it informs how I act with my patients and families today,” Lara said.

It was left to Lara to explain the tough choices her dad was facing.

“I told him that if his heart stopped or he couldn’t breathe on his own, they could put him on life support,” Lara said.

“He said ‘no.’ He told me, ‘It’s OK mija. It’s OK.

Two months after receiving his diagnosis, Lara’s father passed away.

A proud ‘Brown girl’

Lara knows her dad deserved better treatment. So do other patients who don’t speak English or who are people of color. As a little girl, Lara had the nickname “Morena,” which means dark-skinned girl.

She’s deeply proud of her heritage: as a Brown woman, as a first-generation college and medical student, as a Mexican American and likely, as a person with indigenous roots.

In her role as UCHealth’s medical director for health equity, she’s eager to make things easier for diverse patients and staff members alike.

“We need to make things better for people of color and those who do not have access to health care. I view access to health care as a right, not a privilege,” Lara said.

With her achievements and background, she feels both pride and a duty to ease the path for others.

While her parents had great opportunities, they also faced challenges as immigrants and Spanish speakers.

“There was nobody who looked like us on the mountain. I know there was bias, some element of racism,” Lara said. “Part of the reason our parents wanted my sister and me to speak English was that they had experienced racism. They didn’t want us to go through that.”

Lara is pleased that large institutions, like UCHealth, are doing more to promote diversity, equity and inclusion.

“We’re working to improve access to care and to address technology gaps,” Lara said. “I think about every patient. It’s not just Black or Brown people. It’s refugees. It’s people who live in rural areas or those with limited knowledge of health care. Nor do we translate medical vernacular in ways that everyone can understand.”

Along with access to care, Lara said all people deserve “excellence in patient care.”

It’s long been clear that people of color or those from lower socio-economic backgrounds get sick at higher rates and suffer worse health outcomes.

Lara is eager to better track data and improve the lives of all patients.

‘Hispanic families love to gather – Love language is cooking for people’

Among Lara’s favorite activities outside of work is cooking for people.

“Hispanic families love to gather. Our love language is very much cooking,” Lara said.

“My favorite thing that I make is chile verde.”

Her recipe and technique are extra special because she uses her Grandmother Abbey’s molcajete, a Mexican mortar and pestle.

“It’s tomatillo based. I used jalapenos and serranoes, a lot of cilantro and now that I live in Colorado, I incorporate Pueblo green chiles,” Lara said.

In a nod to her Mexican heritage, she loves using Mayan sea salt.

Lara also is leaning into traditional indigenous skills.

She and her husband, Jody Martinez, are avid hunters. Lara hunts with a bow, meaning she must closely track an animal before she’s close enough to take a shot with her bow. She and Jody always use all the meat from successful hunting trips.

“We won’t kill anything we can’t eat,” Lara said.

A newer skill that she’s learning is called Huichol beading. It’s an ancient Mexican Indian tradition.

“As I’ve gotten older, I want to learn more about my traditions and culture. It keeps me grounded,” Lara said

She uses a porcupine quill and dips it in pine or bee’s wax, then decorates bowls and other objects to make colorful creations.

“The archery, cooking and bead work are all ways for me remember who I am,” Lara said. “I’m proud of my heritage. I’m proud of my culture.”

Learn more about UCHealth’s commitment to the values of respect, fairness and compassion for everyone.