Colorado has the fifth-highest 7-day, per-capita coronavirus case count in the United States, and state forecasters say it’s going to get worse before it gets better. Yet the state’s vaccination rate ranks among the top one-third in the country, with about 72% of the state’s eligible population now fully vaccinated.

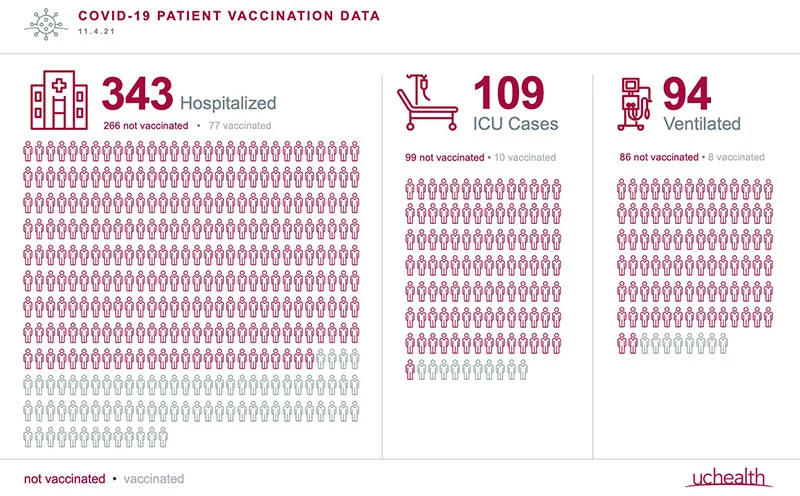

Even as the root of this contradiction remains a mystery, the source of the infection spike now gripping this state is clear. Those who are unvaccinated comprise about 80% of infections. At UCHealth hospitals, that ratio holds: 78% of those hospitalized and 91% of those in ICUs are unvaccinated. The ones hospitalized despite being vaccinated are often immunocompromised or significantly older.

The Delta variant is so contagious that the vaccinated, even if they don’t get as sick as they otherwise would, can catch and potentially spread it. That’s resulted in about one in 51 people in Colorado being infectious – nearly as high as the infection rate during the pandemic’s early, unvaccinated days of 2020. Masks in crowded indoor spaces and booster shots for those who are eligible, should be high priorities, health officials say.

At a Nov. 2 press conference, Gov. Jared Polis painted a stark picture of Colorado’s reality now:

- Among those ages 70 and above – a highly vaccinated cohort – two-thirds of Colorado coronavirus deaths are coming from perhaps 7% of the population.

- No one vaccinated and under 40 has died of COVID-19 in Colorado since July; more than 30 unvaccinated younger people in that cohort have died, Polis said.

- Among those ages 40 to 60, about a dozen who were vaccinated have died since July; among the unvaccinated, 153 have died. Polis’s frustration with the unvaccinated was hard to miss.

“The 20% that haven’t yet chosen to get protected are putting themselves at risk – which you can certainly argue is their own business, and I have no qualm if they have a death wish,” the governor said. “But they’re clogging our hospitals. And I think most Coloradans are sick and tired of trying to protect people who don’t seem to want to protect themselves.”

Surge in Colorado COVID-19 cases has an impact on care

The governor’s frustration echoed that of those on the front lines of Colorado health care.

“If you gave me 10 things I could do to end this pandemic, the first nine would be to get everybody vaccinated,” said Dr. Richard Zane, the head of Emergency Medicine at the CU School of Medicine and UCHealth.

The tenth thing, he added, would be to get as many people as possible who are sick with COVID-19 but not yet hospitalized to get the monoclonal antibodies that have proven about 70% effective in preventing eventual hospitalization, he added.

Zane says the coronavirus surge is challenging hospitals and providers.

“I can’t be more emphatic about this: you’re seeing health care at the breaking point in Colorado. Never in my career has it been busier. Never in my career have people been sicker,” he said.

It’s not just COVID-19 cases, he says. People who put off screening tests and routine care earlier in the pandemic are showing up with kidney failure, heart problems, diabetes complications, and advanced cancers that could have been addressed earlier.

“The acuity is much higher,” Zane says. “Patients require more procedures, more testing, more radiation studies, more consultations, more admissions – because they’re just sicker. And the COVID patients keep coming.”

The crowding of UCHealth University of Colorado Hospital on the Anschutz Medical Campus has a broader effect, he adds. The academic medical center’s depth and diversity of specialists mean it often takes in seriously ill and injured patients transferred from hospitals without such resources. Bringing in those patients is becoming more difficult because the hospital is caring for so many patients with COVID-19.

Statewide limits to elective procedures are again on the table, and “elective procedures” can be anything but. Examples abound, but University of Colorado School of Medicine and UCHealth orthopedic surgeon Dr. Rachel Frank puts one in perspective.

“Let’s say you have a 16-year-old with an ACL tear. If you delay that, you’re subjecting them not only to prolonged inactivity and, potentially, depression but also to possible meniscus damage and arthritis down the road,” she said.

Why is Colorado seeing a spike in COVID-19 cases now?

The simplest reason that Colorado is seeing a leap in coronavirus cases now is that too few people have received at least one shot of the highly effective, extremely safe COVID-19 vaccine. The other part – why are case counts rising now? – is tougher to answer.

Scientists such as Dr. Jonathan Samet, dean of the Colorado School of Public Health and head of the Colorado COVID-19 Modeling Group, have tracked the pandemic and provided forecasts for state leaders.

“We have sifted through explanations for Colorado’s current course but have come up without a very specific explanation,” wrote Samet in an email.

At the Nov. 2 press conference, State Epidemiologist Rachel Herlihy said that, while increased exposures through reopening of restaurants, movie theaters and other social activities have contributed to the increase in cases, it’s not clear why it’s happening more in Colorado than elsewhere. But seasonality may play a role, she said.

“I think it’s more than a coincidence that this is happening at the same time as last year,” Herlihy said, noting that 2020 also saw a peak in hospitalizations in late November and early December – just when this year’s peak is expected. “I think there is something with seasonality, behavior, temperature, humidity – it’s hard to really know what it might be. But it does seem like there is some element of seasonality going on here.”

Zane suspects that the state’s uneven vaccination rates across its 64 counties are a contributor. Colorado counties’ rates of vaccination among eligible residents who have received at least one shot range from 100% in San Juan County to 37% in Washington County. While populous counties are generally better vaccinated, there’s a range there, too: 86% in Denver County, 82% in Jefferson County, 75% in Larimer County, 71% in El Paso County, and 65% in Pueblo County. It may be no coincidence that the combination of a sizable population and a low vaccination rate is contributing to Pueblo County having the state’s worst coronavirus spike. Herlihy pegged the rate of infection among the unvaccinated at between eight times and 20 times that of the vaccinated.

“It’s really giant holes of unvaccinated people, and gives the virus the opportunity to spread like wildfire,” Zane said.

For Zane and colleagues, the disconnect between the extraordinary stresses that hospitals are enduring and the relative normalcy outside of them is striking.

“People are behaving as though this is not happening,” he said.