When Craig Overman’s Parkinson’s medications no longer kept his symptoms under control, he became a textbook candidate for deep-brain stimulation or DBS.

Then, he benefited from treatments so new that they’re not even in medical textbooks yet.

Remote deep-brain stimulation for Parkinson’s disease

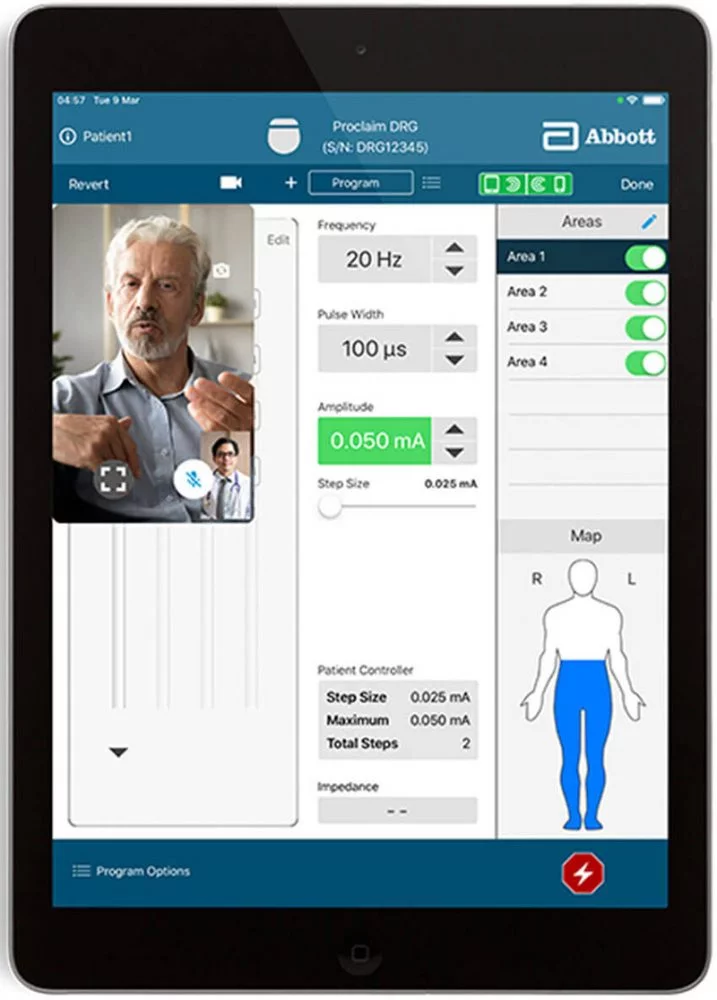

That cutting-edge technology, approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in March, enables remote programming and adjustment of the electrical stimulation that makes deep-brain stimulation work.

For Overman and his wife Susan, who live in Wyoming, a five-and-a-half-hour drive from UCHealth University of Colorado Hospital on the Anschutz Medical Campus, fewer trips to the hospital have been a particular blessing.

“It has saved me time and money,” Craig said.

The deep-brain stimulation itself has saved him much more than that.

The Overmans live in Newcastle, Wyoming. Craig, now 62, had operated heavy equipment in open-pit coal mines for 37 years as of 2015. That’s when a friend noticed that Craig’s left arm wasn’t swinging when he walked. A visit to a neurologist brought the diagnosis of early-stage Parkinson’s disease. Craig went on with his life until Parkinson’s made that hard to do.

In his case, the symptoms were mainly manifesting in fluctuations of muscle rigidity and involuntary movements of the arms and legs, which is known as dyskinesia. The go-to Parkinson’s drug, levodopa, helped, but as time passed, the fluctuations were more frequent and unpredictable. That led to higher and more frequent doses of levodopa until Craig was taking 20 pills a day – more than twice as much of the drug as patients typically take.

Parkinson’s disease symptoms creep in

Meanwhile, Craig’s health deteriorated. By 2016, his ability to operate equipment that makes full-sized pickups look like Tonka trucks was no longer possible, and he went on disability. Walking became increasingly difficult, to the point that a walker, and, later, an electric wheelchair, came into play. An expert archer and bowhunter, Craig found himself unable to handle his bow. Other activities he loved – camping, four-wheeling in the Black Hills, fishing with his grandson Hayden – suddenly seemed out of reach. Fatigue and sleep problems, common Parkinson’s symptoms, crept in. Making matters worse, the levodopa played havoc with his digestive system.

“He couldn’t eat, wouldn’t eat,” Susan recalled.

As so often happens, physical challenges brought psychological barriers, and justifiably. Craig couldn’t walk into a store and be entirely sure he would be able to walk back out of it because, as he put it, “my muscles would just stiffen up.” Craig started skipping his grandson’s youth baseball and basketball games – games he loved to watch – for the same reason. He increasingly ended up watching a lot of TV by himself.

“I had no ambition. Things I really enjoyed, I didn’t want to do anymore,” Craig said.

Susan, working full-time as the treasurer of Weston County, never quite knew what to expect upon returning from work.

“You never knew if you were going to come home to him lying on the floor,” she said. “One time, the ambulance had come. There were several trips to the ER because he wasn’t feeling good and having issues with different things.”

Enter deep-brain stimulation for Parkinson’s disease

Craig was aware of deep-brain stimulation or DBS, but wasn’t enthusiastic about the notion. YouTube wasn’t helping.

“I went to the internet and started the videos of the surgeries, and I couldn’t finish watching them,” he said.

By April 2020, though, he knew something had to change. Craig’s neurologist in Rapid City, South Dakota, referred him to Dr. Drew Kern, a University of Colorado School of Medicine and UCHealth movement-disorders neurologist.

After an in-depth discussion with Kern on advanced therapies, Craig and Sandy made the decision to pursue deep-brain stimulation. Determining who is a good candidate for DBS is vital and involves comprehensive testing over two days. During this time, Craig also met with Dr. Steven Ojemann, a fellowship-trained stereotactic functional neurosurgeon at UCHealth University of Colorado. Ojemann has 20 years of experience in DBS, the most in the region. The entire DBS team, including nearly 20 clinicians and other providers, reviewed Craig’s candidacy the following week.

And, they determined that DBS would work well for him.

Craig’s Parkinson’s disease manifested in the sorts of motor complications – in particular, dyskinesia and muscle rigidity – that DBS works best on. Also, Craig’s stark “on-off” fluctuations as the levodopa pills wore off were a sign that DBS should work well. Further, when the levodopa was “on,” it drastically improved Craig’s motor skills.

“The benefits of DBS can be predicted based on the effects of medication,” Kern explained. “He had a 70% improvement of his motor performance with medication; however, the duration was shorter than ideal and he had bothersome dyskinesias.”

Importantly, Parkinson’s disease hadn’t affected Craig’s cognitive state, which DBS doesn’t improve. And he was still young, had no serious comorbidities, and had strong family and social support, as the CU DBS saw it. DBS was a go.

Precise placement during DBS surgery

But the procedure would have to wait. The coronavirus pandemic shut down elective surgeries across Colorado, then throttled them back later in 2020. It would be January 2021 until the procedures took place.

Deep-brain stimulation surgery for Craig involved three procedures. During the first and second, doctors implanted the electrodes on the right and left sides of Craig’s brain. During the third procedure, the specialists placed the battery under the skin just below the collarbone.

Three subspecialists collaborated prior to and in the operating room for placement of the DBS electrodes: the movement-disorders neurologist ( Kern), the neurophysiologist who aides in determining the location of the electrode based upon hearing and watching brain cells fire (Dr. John Thompson)); and the stereotactic functional neurosurgeon (Ojemann). University of Colorado Hospital is among a select few U.S. medical centers bringing such a comprehensive array of skills to the DBS operating room.

During those first two surgeries, the trio precisely placed DBS electrodes in Craig’s subthalamic nucleus. Craig was awake for both: his movements and responses improved targeting and helped avoid adverse effects. During these surgeries, the DBS team combines intraoperative imaging, neurophysiology, and clinical response to accurately position the electrodes. In the event that the patient can’t be awake for surgery, the team also does DBS under anesthesia using an MRI-assisted system called ClearPoint that combines real-time MRI guidance in the implantation of DBS electrodes.

In early April, the Overmans were back at the hospital for Kern to program the DBS device. This was one of the several 330-mile trips he had already made. Programming involves adjusting the amount and location of electrical current flowing to Craig’s subthalamic nucleus. Susan took cell phone videos of her husband walking down a hallway before and after the roughly 90-minute session. Before, he shuffles slowly and stiffly with baby steps; after, his strides are healthy and his gait appears nearly normal.

On the way home, a snowstorm hit, and as the Overmans followed a snowplow the last 35 miles up U.S. 85, they both looked forward to not doing this drive too many more times.

Remote programming of deep-brain stimulation

The Deep-brain stimulation team at University of Colorado Hospital involves its patients in the choice of hardware to be implanted: Medtronic, Boston Scientific, or Abbott. Each of these device companies offers excellent products but there are some differences, which would make an individual choose one over the other being specific for this person’s lifestyle.

For Craig, he chose Abbott as it was not rechargeable and at the time may have the ability to be programmed remotely. Between the DBS surgeries in January and the initial programming in April, Abbott did receive FDA approval for a system enabling the remote programming and adjustment of Craig’s controller.

Craig could use an iPhone or iPad to connect with Kern or a nurse. Using secure video links over Wi-Fi or cellular networks, UCHealth providers could do telehealth visits, observing as Craig did finger taps, toe taps, walked, and so on, and make programming adjustments just as if he was in the same room with the physician. Kern even received a medical license in Wyoming to be able to do such remote consultations.

The Overmans made two more trips to Aurora, neither of which involved snowstorms. By then, Kern was satisfied that they could do the next visit at a distance. In mid-May, Kern and Craig video chatted, Craig did some prescribed movements, and Kern made some minor adjustments. Craig was the first patient in the region to receive remote DBS programming. Kern and Craig have had subsequent remote programming appointments and will continue to do so going forward.

Remote programming and adjustment could work just as well for someone 300 miles or even three miles from Aurora, Kern says, and other patients have since chosen the telehealth option. He offers it to everyone, he says. But there are some minor limitations: It’s harder to gauge gait over a video link, and it’s not possible for him to feel for muscle rigidity. Some patients, particularly ones closer to Aurora, may continue to prefer onsite visits. But many others will surely opt for remote adjustments.

Craig Overman is back at his grandson’s games, and his health has returned in time to support another grandchild’s youth-sports endeavors: granddaughter Payton is getting into soccer and basketball. Craig is also looking forward to fishing, hunting, and four-wheeling. He’s cut his levodopa dosage by about 75%, has his appetite back, and is feeling a whole lot more energetic.

“I mean, he’s been doing everything,” Susan said. “The other day, he power washed the deck and he stained it, and we’re getting new windows, and he’s out mowing the lawn.”

Craig marvels at what DBS has done for him.

“It’s changed my life for the better, and it’s only been three months,” he said.