Celia de Santiago is blind in one eye after complications from cataract surgery in Mexico, and now she is losing vision in her other eye because of advanced diabetic retinopathy.

Celia and her husband, Armando, have no health insurance even though they have lived and worked in the U.S. for nearly 30 years.

Armando, 70, earns a little too much from his job as a dishwasher and from his Social Security benefits to qualify for Medicaid. Yet the couple can’t afford private insurance.

So, like many uninsured people, they struggle to find medical care. It’s especially hard to find help from specialists like eye doctors.

Yet, on a Monday evening in a community center in Aurora, Celia, 60, was able to get care from a retinal specialist, a retired retina specialist, an ophthalmology resident, and a team of nursing and medical students, who regularly provide care to the uninsured at the DAWN Clinic.

“It’s good they’re helping me,” Celia said. “They take good care of me.

The clinic is housed in the Dayton Street Opportunity Center just off East Colfax Avenue and Dayton Street in an area of Aurora with some of the highest poverty levels in Colorado and a disproportionate percentage of uninsured people. Students from the University of Colorado across an array of fields from nursing to medicine to dentistry and physical therapy at the nearby Anschutz Medical Campus run the clinic.

DAWN has provided primary care one evening a week for about four years and recently the clinic has added specialty care in tough-to-access areas like ophthalmology, cardiology and dermatology.

A full day’s work, then an evening of service

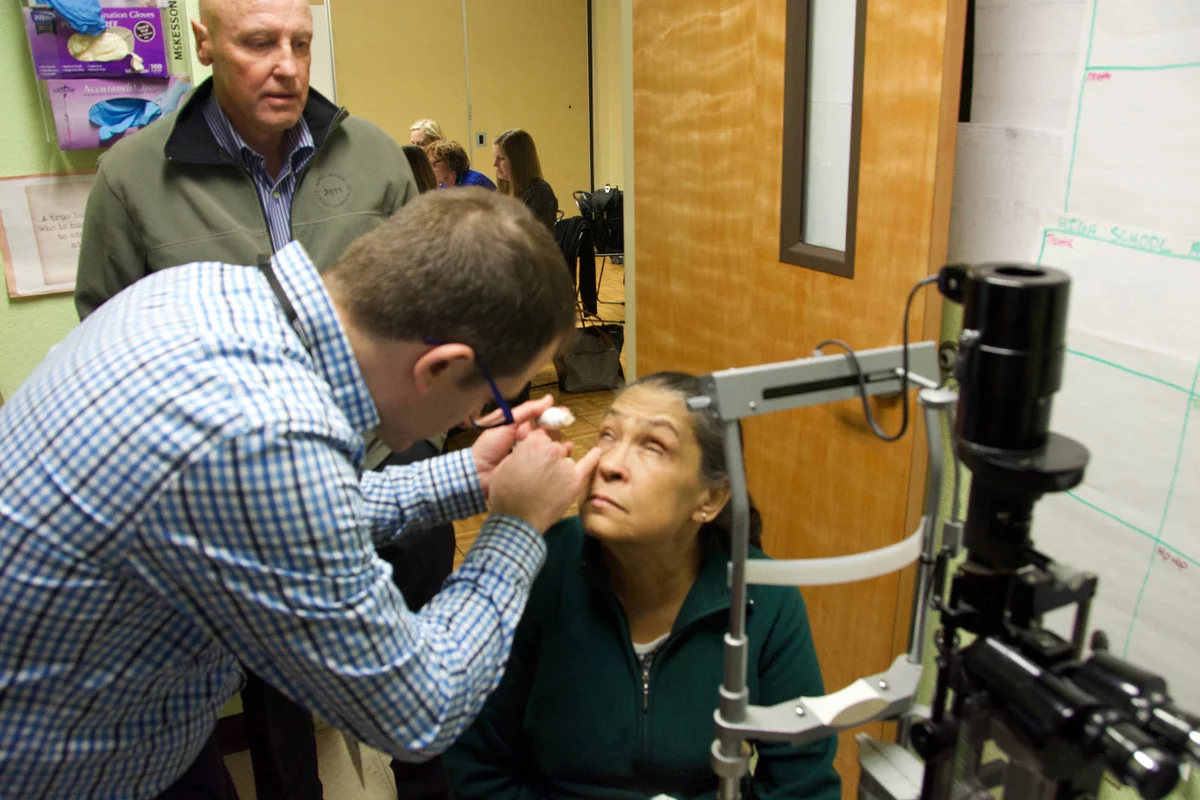

In a makeshift exam room, Celia sits in a chair and rests her chin on a high quality donated exam tool called a slit lamp.

Then, two pros take a look at her right eye.

Dr. Frank Siringo is a retinal specialist who usually practices at the Sue Anschutz-Rodgers Eye Center.

He is exactly the person who can help Celia because the diabetes she has suffered for about 20 years has been poorly treated and she has developed what’s known as proliferative diabetic retinopathy.

Siringo, who is also an assistant professor at the University of Colorado School of Medicine, has already had a full day of work.

Yet, he’s passionate about volunteering his evening to see patients like Celia and has been coming to the once-monthly DAWN clinics since the center started offering ophthalmology care.

“A lot of us lead very privileged lives. We have to be cognizant of those less fortunate. It’s part of the job and we shouldn’t forget about them,” Siringo says.

“We have a very big state-of-the-art hospital center about a mile-and-a-half from here. It’s important to look on the other side of Colfax and help the community,” Siringo said. “A lot of the work is helping people get plugged into services that are available in the community, but you have to know how to access them.”

Siringo speaks in Spanish to his patient as he compares notes with a fellow volunteer, Dr. Bill Mestrezat, who moved to Colorado to retire after 40 years working as a retina specialist in Michigan and Florida.

Celia had come in for an eye exam at the DAWN Clinic last month and both men noticed significant bleeding and scarring in her eye at that visit. This time, the bleeding has improved. Nonetheless, both agree that she will need surgery. The DAWN team will try to make that possible.

“The vision in her right eye is very tenuous right now,” Siringo said. “She could see some of the bigger letters on the eye chart, but she needs surgery to clear out the scar tissue and remaining blood, plus laser therapy to prevent it from recurring. She could get a good amount of vision back.”

He said it’s troubling to think how many other patients like Celia are going untreated.

“This is a problem that’s preventable and treatable. I walk in and two minutes later, there’s somebody sitting here who needs my help. There are probably many, many more within a two mile radius,” Siringo said.

Like Siringo, Mestrezat loves volunteering and assisting students in caring for patients with complex medical challenges.

“This helps me give back. The biggest challenge is getting people help when they have nothing,” Mestrezat said. “Diabetes is probably the No. 1 cause of blindness in people under 60. It damages the blood vessels and causes them to leak or bleed.”

‘Life or death care’

Molly Turner is a nursing student due to graduate with her undergraduate degree in May. She’s one of the leaders who helps organize the specialty clinics.

“We have ophthalmology and diabetes along with dental, cardiology and pulmonology. We have a big presence of tuberculosis here in Aurora,” Turner said.

In addition to arranging for the specialists, the students bring in interpreters to assist during the appointments along with care coordinators who ensure that patients get the assistance they need following their medical appointments.

“Celia is a prime example of what DAWN is all about: providing a safety net facility to truly help a member of our community,” Turner said.

Sally Garcia is a nurse and the only staff member at DAWN. She works part-time at DAWN and part-time doing research in the Labor and Delivery unit at UCHealth.

Garcia said the specialty care is essential for many patients.

“For some, it’s life or death. We have patients who are very, very sick with congestive heart failure. For them, having the ability to have someone come in and lay eyes on them and provide the most up-to-date care is huge,” Garcia said.

She said one patient would have died without help without care from a specialist.

“He’s doing well and is working again,” Garcia said.

Garcia gives all her high-need patients her cell number and they can call if they think they’re having a medical emergency.

“A huge part of what we do is keep people out of the Emergency Department (if they don’t have an emergency). I’m on call 24/7 and all of our high-risk patients have my number,” Garcia said. “There’s no ask-a-nurse phone number for these folks.”

Often Garcia said she can talk patients through a crisis and arrange to get them non-emergency help that they need.

After patients see medical providers in the clinic, Garcia and the students do all they can to try to help patients get surgeries or other follow-up care that they need.

‘They take good care of me’

Celia and Armando de Santiago are quiet, patient and grateful as they weave their way through the stations at the clinic.

They come to the DAWN center for other care as well. Celia’s kidneys are failing because of her diabetes and Garcia has also helped her access dialysis three times a week that she began getting earlier this year.

“They treat us well. They’re nice and the patients are happy,” Celia said. “I hope that after my surgery, I will be able to see.”