Unless you happen to subsist on sulfur in a deep-sea vent, the sun is why you’re alive. Yet for too many, and despite decades of experts’ stressing the risks of exposure to the sun and its thousands of earthbound tanning-bed proxies, real and synthetic sunlight brings life to a premature end. A team at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus this month launched a two-year, $800,000 campaign aimed at jolting a demographic that tends to view itself as invincible into behavior change that can ultimately save its skin.

We’re talking about college students. The campaign, led by CU School of Public Health Professor Lori Crane, PhD, MPH, and paid for by the state health department, will touch about 170,000 students on 10 college campuses across Colorado and in areas directly served by UCHealth (see box). It will combine grassroots community building, technologies as fancy as ultraviolet (UV) cameras and as basic as sunscreen in strategically placed bottles, and good-old-fashioned policy and education initiatives.

The goal is more than merely to educate on how sun and skin – beyond minimal, vitamin D-building exposure, at least – don’t mix, though that’s a big part of it. Rather, it’s to foster campus norms, and by extension societal ones, that will serve as a new kind of sun block.

Troubling numbers

The data on the adverse health impacts of UV light exposure is as voluminous as it is troubling. A sampling, courtesy of Crane and colleagues: melanoma, the deadliest form of skin cancer, now represents the third most common cancer among 15- to 39-year-olds. Colorado, a melanoma hot spot with a mortality rate 30 percent higher than the national average, had 1,400 diagnoses and 160 melanoma deaths in 2015. About 5.4 million cases of non-melanoma skin cancer are treated each year in the United States – more than the combined number of breast, prostate, lung and colon cancer cases – with annual costs exceeding $8 billion. Skin cancer will affect one in five Americans at some point, and up to half of everyone who lives to age 65.

Perhaps the most troubling figures relate to tanning beds: About 419,000 skin cancer cases in the United States are linked to indoor tanning each year – including over 6,000 cases of melanoma. That’s more than the number of lung cancer cases linked to cigarettes each year. People who start indoor tanning before age 35 increase their melanoma risk by 75 percent, and indoor tanning boosts risks for squamous cell skin cancer 67 percent and basal cell skin cancer 29 percent.

Universities often abet tanning-bed use, CU and other researchers have found. They let students use student debit cards at tanning salons; they allow tanning salons to advertise in campus publications and pass out coupons on campus; and they refer students to off-campus housing that offer indoor tanning beds as a free amenity, often with unlimited use.

Tamping down indoor tanning is an important part of the campaign, says Nancy Asdigian, PhD, a CU School of Public Health research associate and collaborator on the project.

“We’re trying to wake university communities up,” Asdigian said. “They wouldn’t let cigarette companies come out and pass out coupons.”

Revealing images

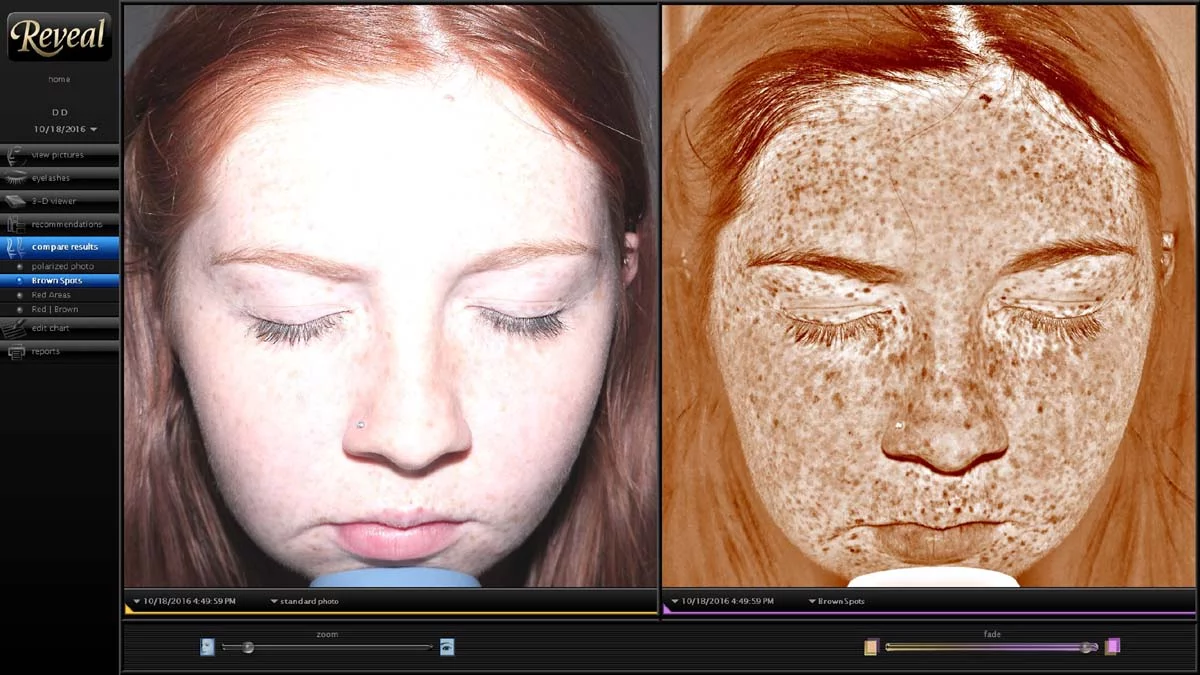

A big part of the wake-up call will involve giving young people firsthand looks at the damage skin has already sustained. It’ll happen thanks to a $6,000 Reveal Imager, which sheds UV light on the subject’s skin and processes it into a picture our eyes can see. Each campus involved in the project will get one to keep, for use during events or however they see fit.

Elsa Weltzien, MPH, 23, a professional research assistant and health educator on the project, volunteered to show how it works. Though she’s got a redhead’s typically fair complexion, Weltzien’s countenance looks pristine to the casual eye. The UV image, though, showed a sea of freckles.

“It’s very interesting, especially because I wear sunscreen every single day,” Weltzien said, checking out the side-by side images on a laptop linked to the Reveal rig. Thanks to her parents, she has shielded herself from the sun for as long as she can remember, too.

Project team member Jessica Mounessa, 25, was at the Reveal Imager’s controls. She’s a fourth-year medical student at Stony Brook University in New York, taking a research year in the CU Department of Dermatology under the wing of Robert Dellavalle, MD, PhD, MSPH, the department’s chief. Dellavalle is the project’s dermatology expert.

Mounessa is darker complected than Weltzien. She too appears to have immaculate skin. “We’re Persians. We don’t even know what sunscreen is,” she quipped. But Mounessa said her UV images also are shockingly freckle-filled.

Cultural change

The shock is part of the point. There may be the occasional young person who has managed to ward off skin damage to the point that even UV light fails to expose it. But that’s the exception.

“People – especially young people – are not motivated by long-term impacts,” Mounessa said. “The UV camera is a very powerful tool. It’s that immediate awareness that, ‘I’ve already been incurring damage to myself.’”

Crane and colleagues hope that awareness will, prompt a receptiveness to the education-and-prevention elements of their program, which are based in part on the Skin Smart Campus Initiative as well as work to develop and assess a web-based sun-smart education curriculum called UV4.me, led by Carolyn Heckman, PhD, of the Fox Chase Cancer Center in Philadelphia.

A big part of the Colorado campaign will be working with student leaders, faculty and administrators to understand the unique opportunities to improve skin protection at the various campuses and coming up with tailored ways to do it. The program is offering $5,000 grants to each campus, which institutions can use to set up artificial shade in common areas, buy sunscreen for public use, and promote suns safety in other ways. Surveys done before and after the program will assess how attitudes across campus change – or don’t. That data should help others who launch similar programs in the future, says Kirsten Black, PhD, MPH, RD, a senior professional research assistant on the project.

Asdigian says there are two main philosophies surrounding sun exposure mitigation. One says a “healthy tan” – an oxymoron if UV-induced – is fine as long it’s sprayed on. The other, where she aligns, sees sun-safe behavior as not only wise from the personal and public health perspectives, but also good for the very diversity that campuses embrace. She’s targeting the mythology associating tanned skin with health and beauty. Among groups such as sororities, cheerleaders, and dance and spirit teams, there’s a tendency toward a sort of common skin hue. That can lead the lighter-skinned to seek tanning beds or sunny campus quads to achieve some real or perceived group consensus on beauty. The price is too high to pay, Asdigian asserts.

“We want to get away from that,” she said. “Let’s be at peace with whatever tone of skin you have.”

The campuses

The two year “Multi-component, Campus-wide Programs to Reduce Environmental, Policy and Behavioral Risks for Skin Cancer at Colleges and Universities in Colorado” will work with a dozen Colorado colleges and universities with 170,000 students on 10 campuses during its two years. The campuses represent 35 percent of Colorado’s population of 18- to 22-year-olds. The CU team is still finalizing its list campuses; the institutions they’re working with now include:

- Auraria Denver Campus (University of Colorado Denver, Metropolitan State University of Denver, and Community College of Denver)

- University of Denver

- Colorado State University-Pueblo

- Colorado Mesa University

- University of Colorado at Boulder

- Colorado State University-Fort Collins

- University of Northern Colorado

- Western State Colorado University

- Fort Lewis College